Donate

Request Help

Українська

About

Since the first days of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, the Kyiv Biennial has launched the Emergency Support Initiative for the members of the artistic and cultural community in Ukraine finding themselves in need. In 2022, our main goal was to support people remaining in the country and to provide them with immediate financial relief under the conditions of occupation and/or relocation.

In cooperation with the Museum Crisis Center, ESI covered urgent needs and supported museum workers on the frontline and in occupied territories in the Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, Chernihiv and Kherson regions where people were left without any governmental support.

Within the first year, ESI has also funded documentary and art projects dedicated to collecting evidence of the war and reflecting on the current situation in Ukraine, provided support to the art residencies in Ukraine that extended their capacities to host those who fled the war zones and provide members of the cultural community with a safe place for life and work.

As the war goes on, we want to remain responsive and thoughtful regarding the issues that seem valuable and the help we can provide. In spring 2023, we are entering the second year of the full-scale war, witnessing the irreversible damage it has caused to many dimensions. This year ESI is focusing on the art and research projects conceived by Ukrainian authors, giving special attention to the planetary impact of the war, supporting the creation of texts, visual and sound projects reflecting on the environmental damage done by military actions in Ukraine.

To continue our work, we rely on the contributions from private donors as well as from partner institutions. We match your donation with requests from the community which we process on the first come, first served basis. By donating, you will contribute towards covering the basic needs of the Ukrainian artists and cultural workers and the costs associated with continuation of artistic practice.

By continuing ESI, we believe to preserve the space for cultural work and creative practices in Ukraine despite the brutal invasion and growing economic crisis, answering these threats with enthusiasm and creativity, spreading the voice of solidarity and nurturing love towards art and culture.

Donate

Please help us support people and institutions affected by the war.

We accept donations via SWIFT transfer, PayPal or Bitcoin. For other ways to donate, please contact us.

Apply

If you are an artist/cultural worker remaining in Ukraine and experiencing hardship, please fill in this brief form to help us best identify the ways we can help.

Stories

Artworks created by Kristina Melnik focus on the body: ravaged by disease or mutilated by violence and elevated to the status of a sacred image. For two years, Kristina’s works were based on war photographs. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion disease has become her major theme.

We talked to Kristina, supported by the ESI as part of its activities, about her art after February 24.

“In the first two months, it was difficult to make anything at all, because for me, the process of creation is about pleasure. I work with sacred images, which requires the kind of sensitivity that takes you beyond the boundaries of the real. At the time, though, I was dealing with the loss of my father and a close friend and spent my days scrolling through the news about the war. Later, I left for a residency in Slovakia and returned to work”.

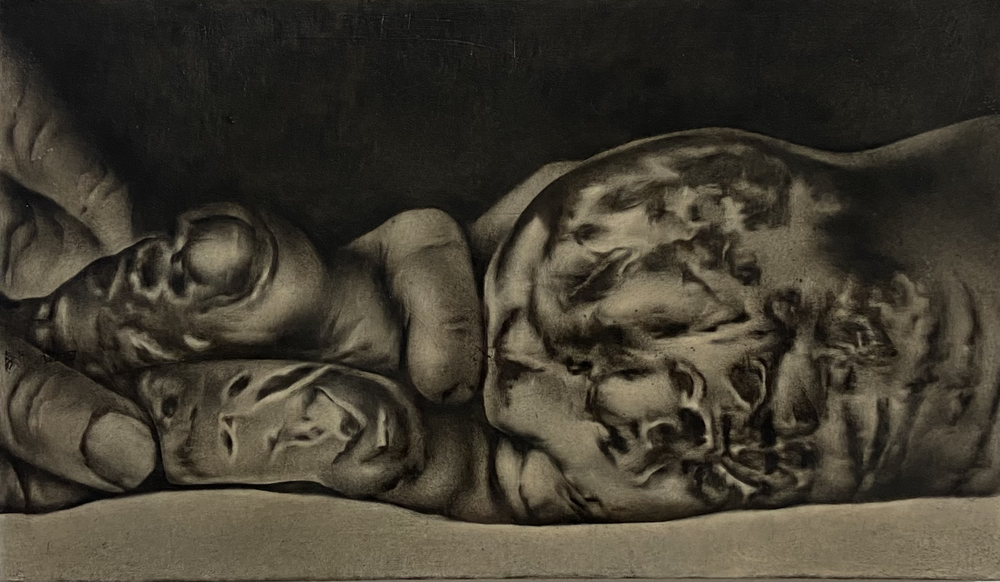

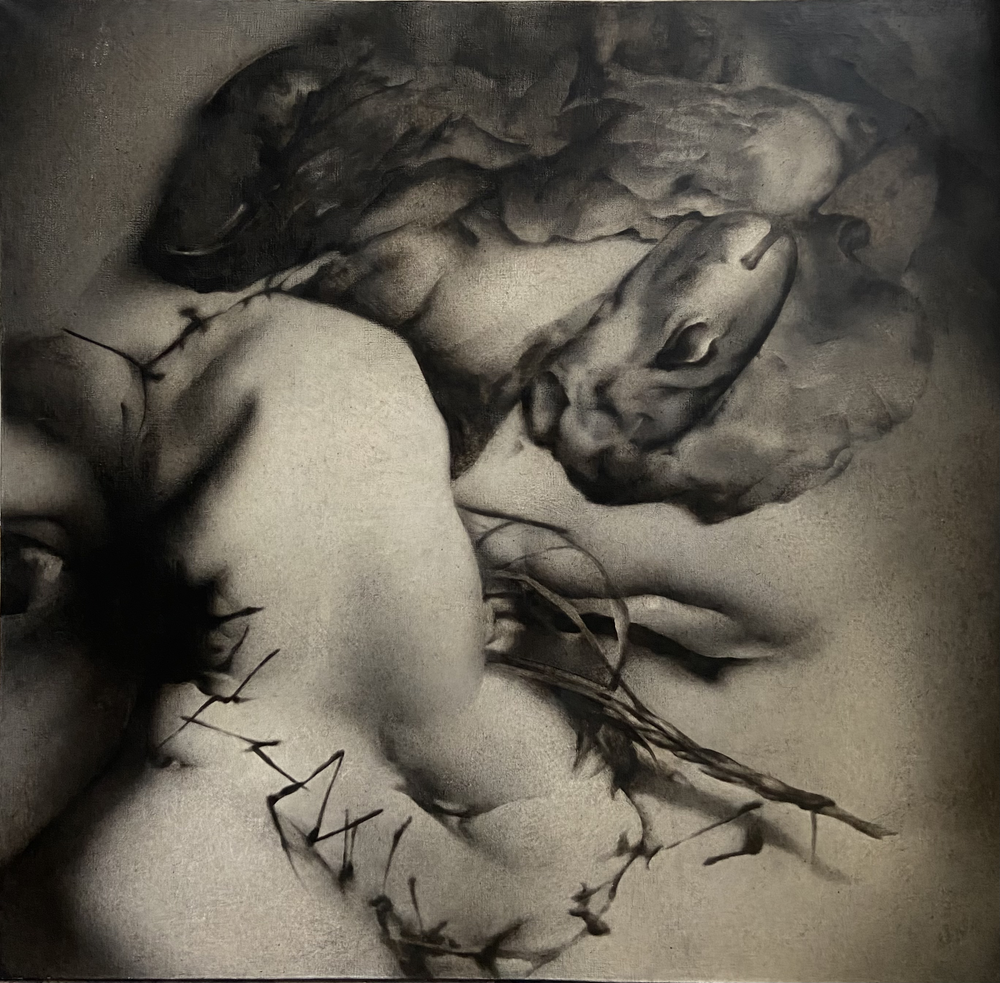

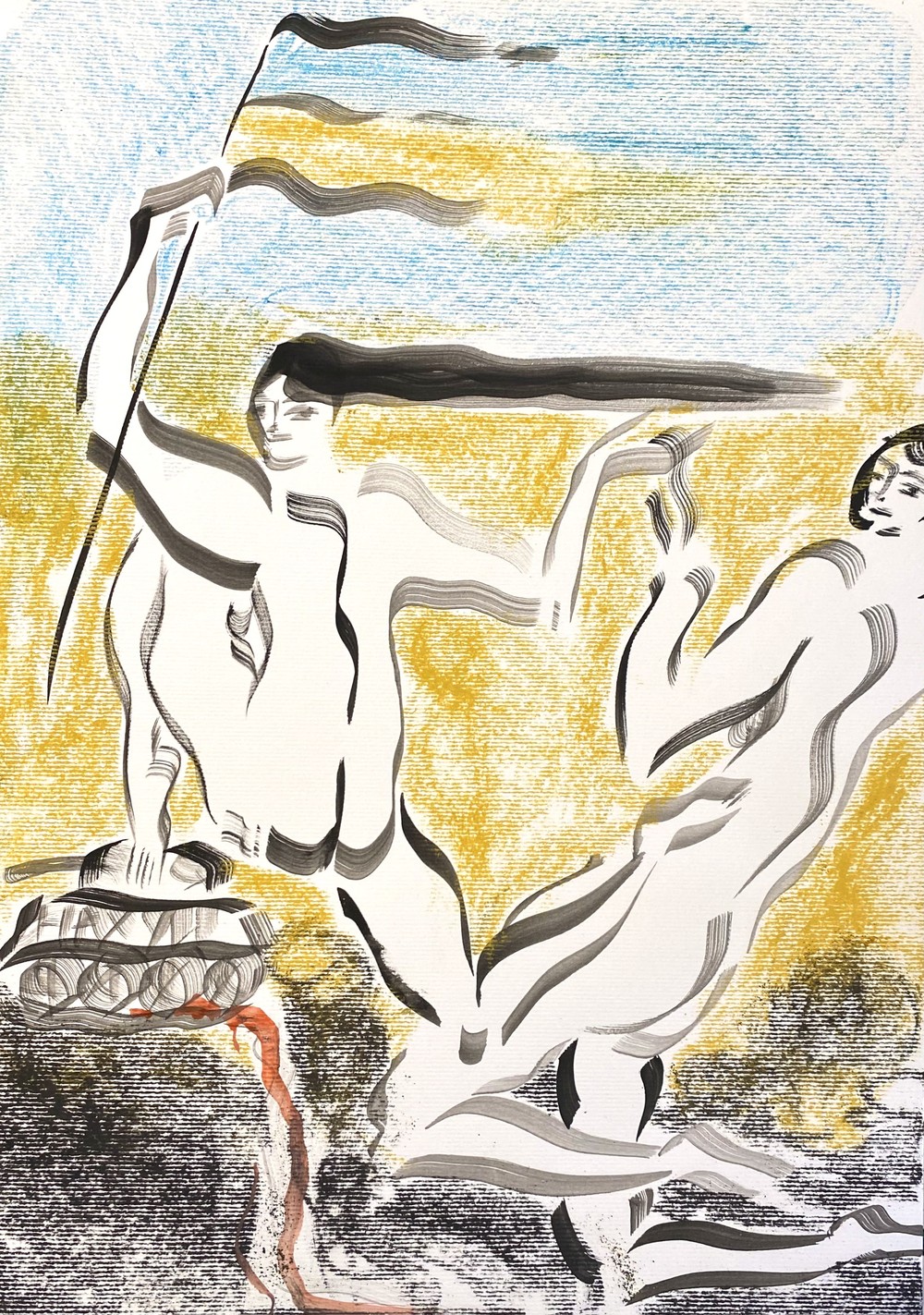

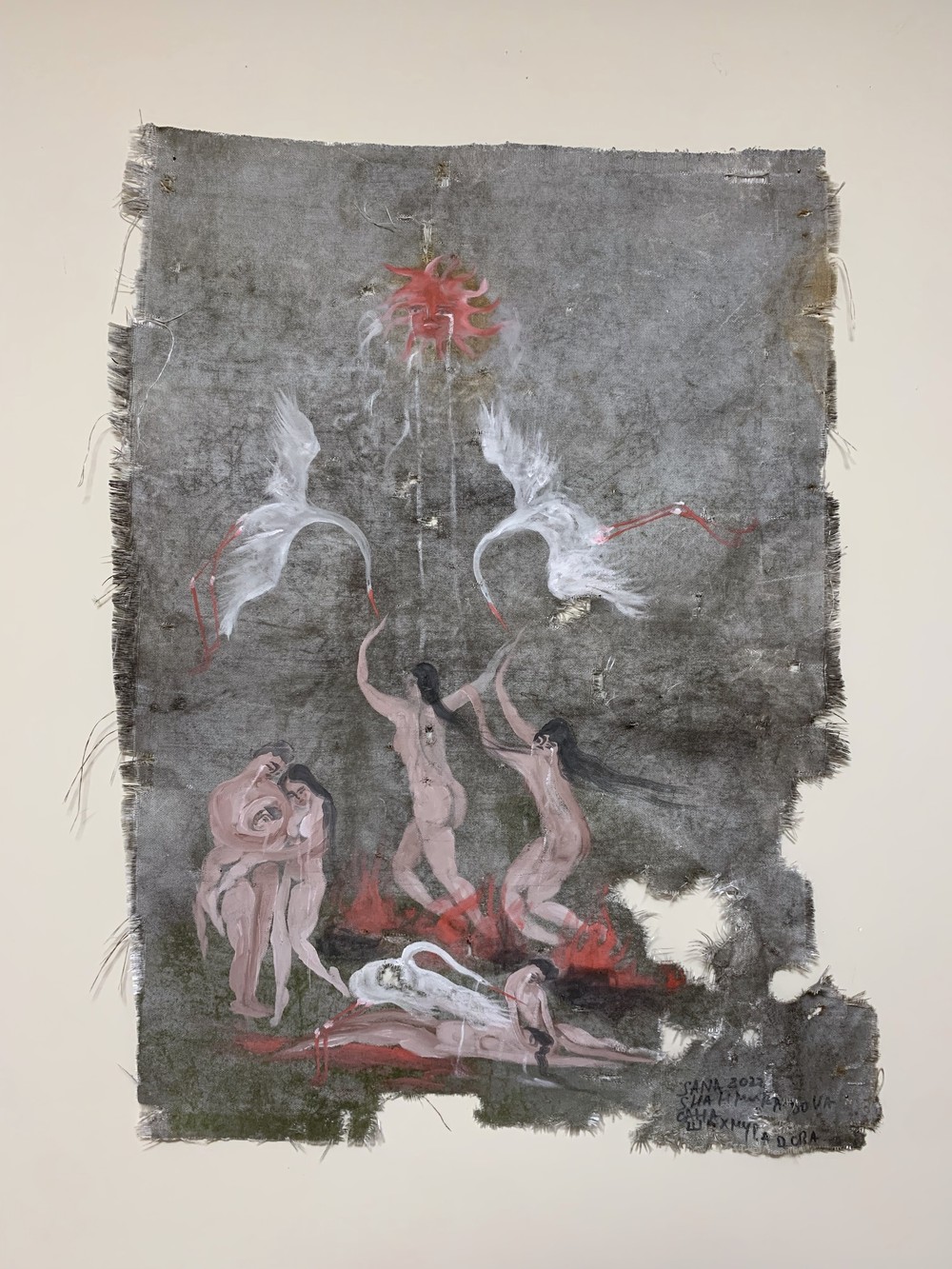

One of Kristina’s pictures is The Angel of History, inspired by Paul Klee's Angelus Novus.

“In Klee's image, the angel’s face is turned to the Past and the wings, to the Future. My picture shows the angel’s back with torn off wings. This piece is about the powerlessness I feel when I confront history and the pain of others. The shape of the female figure in the picture evokes Ancient Greece and the beauty that is no longer possible.

What icon painters do with icons, I do with reality, imbuing images with the expressiveness and sensitivity characteristic of sacred art. Previously, my art reflected on violence one person commits against another; after the start of the war, I was drawn to images of disease. War and disease are closely related, it's about the destruction of the body from the inside. I think that's a potent symbol of what's happening.

To some extent, my work is permeated with the sense of God’s presence. This divine presence does not form the context of my art, though. Rather, it is manifested as a symbol, an image, as the sensory experience of a suffering body. This is the focus of my recent work Seen by God, or Calling for Mercy. The image itself and the title of the work make the viewer wonder: does the picture show us an event seen by God, or His suffering face?”

Kristina returned to Kyiv in mid-summer. Between power outages, she works in the studio and at home, joking that her life turned into a quest: trying to make work possible.

"In circumstances like these you feel the moment you are living through so overwhelmingly that time seems to stretch. Once, I simply went to the store and felt as if moving through liquid. This surprised me a lot. This sense of presence is thrilling, but also incredibly exhausting".

The angel of history.

The one who broke the wings came again

The ones who step on the flowers came again.

Beauty Stydio, an art laboratory located in the Mykolaiv region, combines volunteering and the exploration of beauty. Artists participating in the laboratory work with fragments of destroyed equipment and industrial waste and search for ways to understand others through help.

We spoke to Pavlo Klymenko, curator of the association, about beauty in territories near the frontline and how art and volunteering can be combined.

“For the first 4 months, we were settling into volunteering and figuring out how we could apply our skills to new tasks. It was only later that we came up with the idea of creating an art association. We kept the original name of the space we are working in, Beauty Stydio, because we realized it encapsulates what we are doing here: looking for the elusive beauty”.

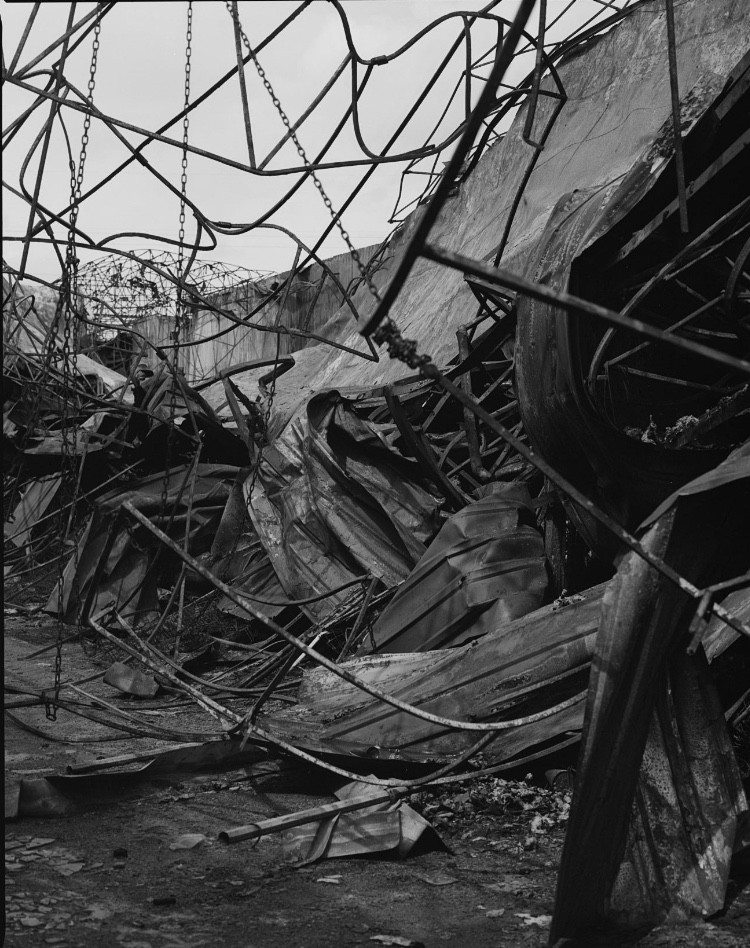

Currently, Pavlo and Maksym Svitlo, another curator of the laboratory, are making sculptures out of enemy equipment fragments. These objects comment on the production and recycling of waste and embody the idea of elusive beauty that underlies the activities of the association.

“When we talk about beauty today, we mean the kind of beauty found in the combination of objects. Two things of different origin that have nothing in common can fit together perfectly”.

Maksym has also worked with fragments of military equipment while creating the Phoenix sculpture. Thanks to the activists’ efforts, the sculpture, like many other pieces, has been auctioned off in order to raise money for the military.

Art lab residents also help people with everyday issues. While accompanying foreign journalists on their trip, Maksym Svitlo met Klava, an elderly woman from Kherson, who invited him to visit her place. The next day Maksym fixed a window in her apartment. He also documented this in a small-scale photo project.

“It happened spontaneously, but it is up to us to do this on a regular basis; we can go and help people who need our assistance once a week.

All in all, it seems to me that we have never stopped producing art since the start of the full-scale invasion. When I make, say or think up something that helps others on a practical or emotional level, gives them a resource, that’s art. That’s how I see its purpose”.

In addition to Pavlo and Maksym, permanent residents of the art lab include DJ roku roku suzu and Vlas Zabolotnyi. Journalists and artists from other cities often stay here as well.

The ESI fund helped the art lab to purchase batteries and spotlights to enable work during power cuts.

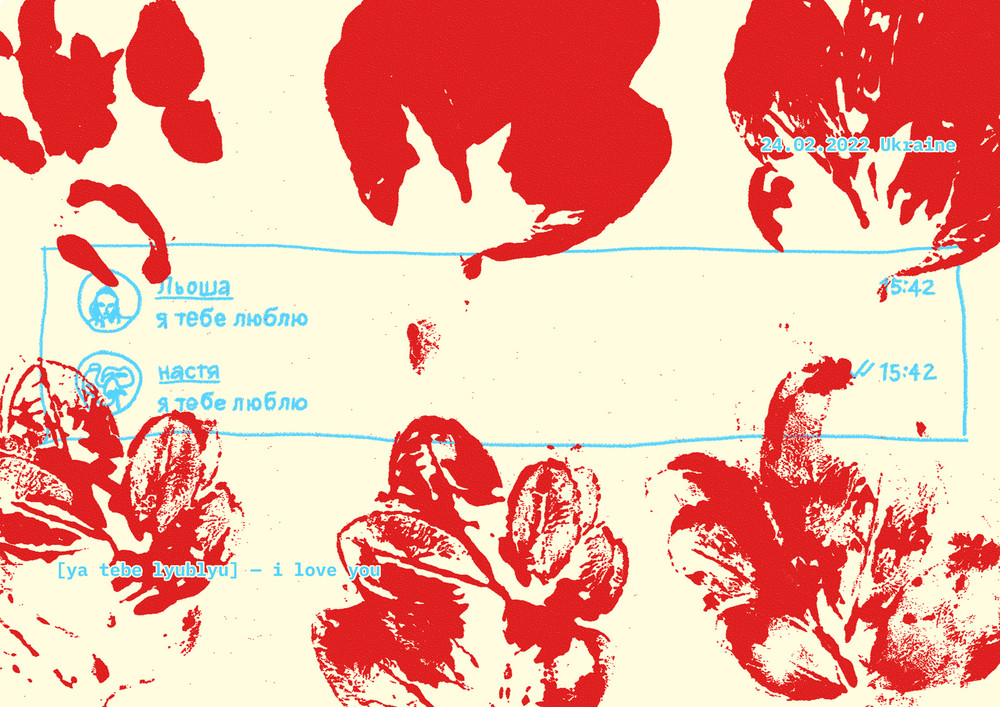

Nova Kakhovka is a city in the Kherson region located between the Kakhovka HPP and the Crimean Canal, 60 kilometers from the peninsula itself. It has now been occupied by russia for ten months. In her works, the artist Viktoriia Rozentsveih, whom we supported in the course of ESI activities, explores everyday life changes, enemy and de-occupation strikes and events in a city that is impossible to get into.

Nova Kakhovka is the artist’s hometown; she planned to return there after graduating from the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture. Instead, she relocated to the Lviv region, went to Germany and then returned to Kyiv. During this time, Viktoriia created three projects about the occupation of Nova Kakhovka.

“It’s hard to talk about home when you can’t go there. But it brings a kind of healing as well: you feel you belong there, and talking about the city helps both you and the city itself”.

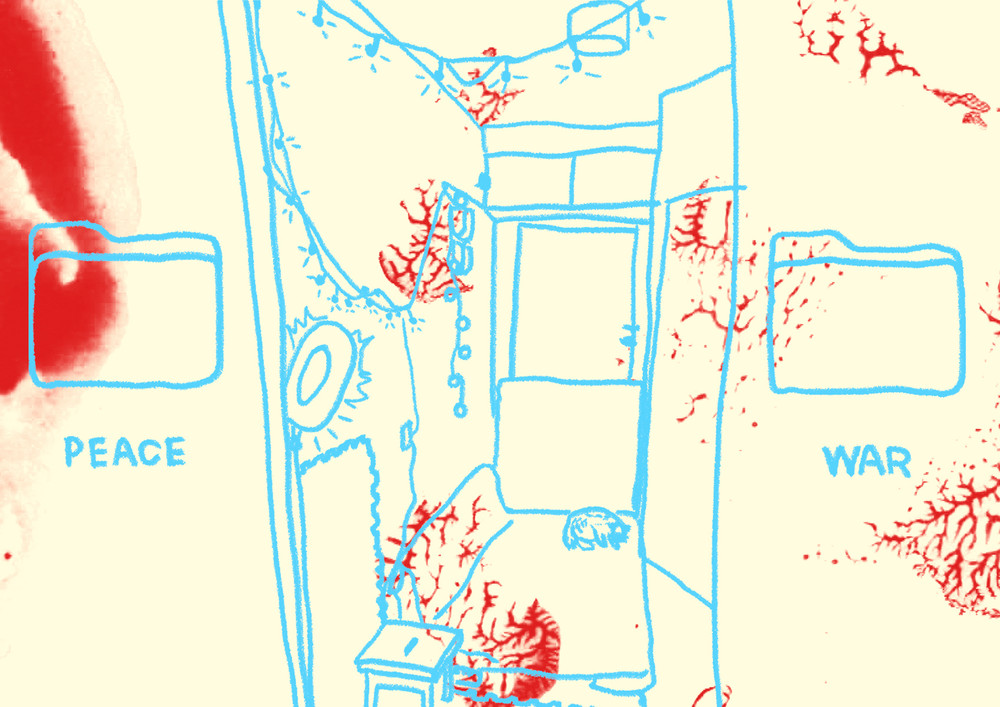

Viktoriia’s first project tells us about the occupation through the lens of political and everyday changes in Nova Kakhovka. The illustrations are based on photos from local chats: a Lenin statue erected in the city, the celebration of May 9. Other pictures convey stories of everyday life as shared by relatives over the phone: the artist’s sister is doing her homework in the corridor; long queues; farmers giving their produce away for free.

The artist is currently working on two projects, Documentation and Incoming, about missiles and projectiles hitting the occupied territories. In the drawings, the results of hits in Nova Kakhovka are depicted on a small scale, but the explosion clouds look huge. In this way, Viktoriia tries to depict the conflicting reactions these strikes cause.

“When explosions happen on free Ukrainian territory, it’s because of strikes carried out by the occupier, it always means loss. When a missile or a projectile hits the occupied territories, this is mostly Ukrainian military targeting the occupiers’ equipment and troops. And you know that this is good, it brings the de-occupation closer, but you also think about your relatives who live nearby. What if the explosion smashed their windows? What if they were somehow affected? What if one of them is buried under the rubble now?”

These projects relate the experiences of those who left, of those whose relatives are in the occupied territories. They are an attempt to articulate and discuss this experience.

“My drawings should be displayed in sheet protectors, like pieces of documentation. In the video, I illuminate them the flashlight on my phone, thus creating a projection that can be enlarged or made smaller depending on the impact of the explosion”.

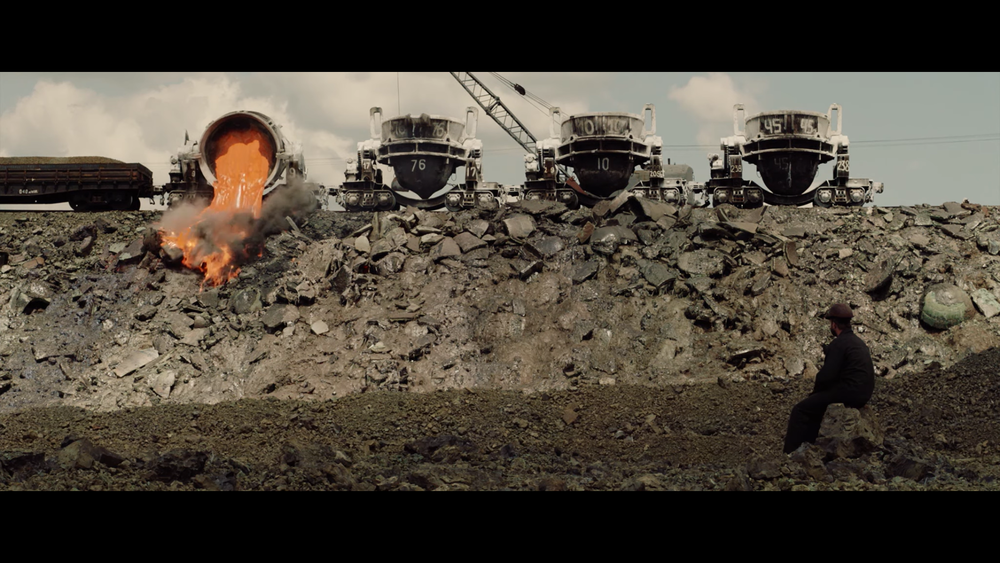

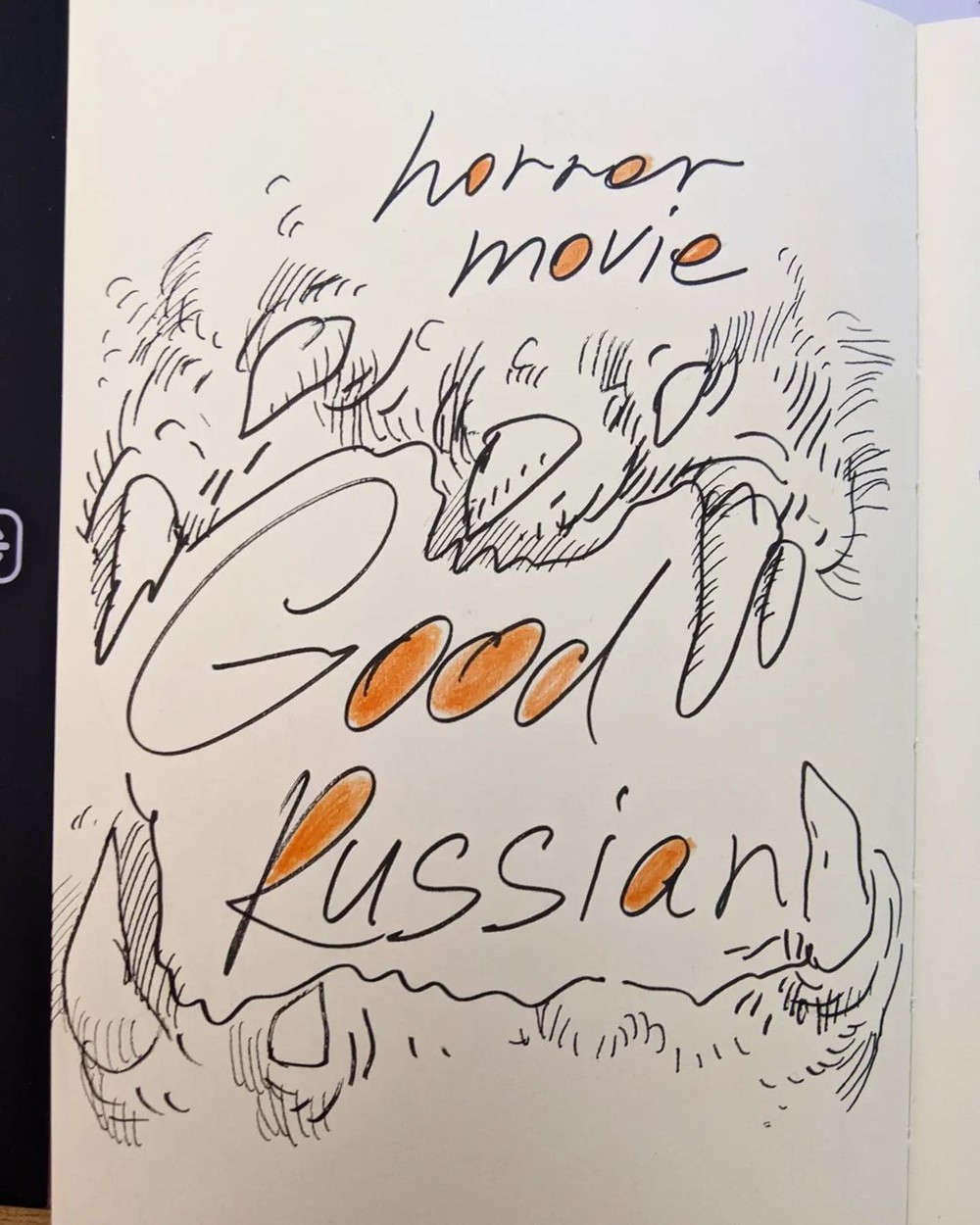

“Ukrainian feature film production is at a standstill. The focus is on documentaries. To make a feature film, you need a lot of money, which we do not have at the moment. But we keep working”, says Vladlen Odudenko, the production designer who worked on such films as Atlantis, Homeward and Luxembourg, Luxembourg.

We spoke to Vladlen about the state of things in the Ukrainian film industry and his own activities during the full-scale invasion.

“In the first weeks of the invasion, Valentyn Vasianovych (the director of Atlantis and Reflection) and I applied for the Armed Forces of Ukraine press cards as independent filmmakers, joined a group of our film industry friends and started working. We were not allowed to get very close to the hostilities but tried to document the wartime reality as much as we could. For instance, we filmed evacuation from Bucha”.

“Then Vasianovych came up with the idea of a documentary about Andrii Rymaruk, a veteran of the Russian-Ukrainian war and a military expert. He played the main role in Atlantis, where events take place a year after the end of the war. In one of the first scenes of the film, we see Andrii’s character in his bombed-out apartment. In the spring we visited Andrii’s actual apartment in Bucha and experienced déjà vu: things we filmed a few years ago happened in real life”.

Like many other projects in Ukrainian film industry, this one is currently frozen. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Vladlen has not worked as a production designer. However, thanks to the support he received from our foundation and other sources, Vladlen is now writing the script of his own short film and gathering materials for the project. This will be his second film as a director.

“I have seen many news reports about children born in bomb shelters. That’s how I got the idea for this film, Alive. Two soldiers in the Kyiv region are gathering dead bodies lying in the streets. They put them into body bags and take them to the basement of a house that survived hostilities. Once there, the soldiers suddenly realise that one of the body bags is moving: the woman inside is alive. She has gone into labour”.

“It’s an intimate emotional story about wartime miracles, about the emergence of hope”.

“I will do my best to make this film, although it’s going to be a challenge, as feature film production is expensive. But it’s true what they say: we need to do what we can to ensure Ukraine’s victory. There’s a reason why I chose this title for the film. I think that filmmakers have to work in order to show that we are alive, we cannot be broken”.

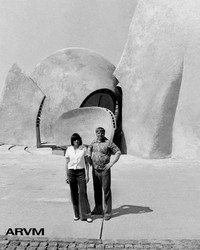

As part of our initiative, we have supported Arwm fund, which works on preserving the heritage of Ukrainian artists Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnichenko. Kseniia Kravtsova, head of the foundation, spoke to us about the organisation’s activities since the invasion.

On February 24, Kseniia and her family started off in the direction of the Carpathians. Volodymyr Melnichenko travelled with them, leaving behind his workshop, which he simply locked. Within a week, Ksenia’s husband Innokentii returned to the capital to save the artworks in the artists’ studio.

“All Ada’s and Volodymyr’s works are stored in the workshop, the artists have never sold them. We are talking about 6,000 pieces. A missile hit would have been a tragedy. My husband hid part of the works in the basement and took some to the west of the country.”

Kseniia evacuated part of the ARVM works to Vienna, where an exhibition dedicated to the Nenets, an indigenous people from the north of Russia, was organised. In the 1950s–1970s, Rybachuk and Melnichenko experienced the Nenets culture first-hand: they lived in nomadic tents, went hunting, ate raw meat. The artists depicted the ethnic group’s way of life in the painting Hunting Song and in other works.

What happened to the Nenets is a classic story of Russian colonialism. The authorities evicted the entire people from the island where the Nenets lived and used it as a nuclear test site and an oil field. The land was turned into a nuclear test range. This is the subject of Explosion on Malaia Zemlia.

“This painting centres on the suffering of the earth. It’s covered with cracks. Inside, a sea beast is screaming in pain, mourning the deaths of birds and animals.”

In March, Melnichenko and Innokentii returned to Kyiv and continued cataloguing the art pieces in the workshop. Later, the museum started sheltering people who lost their homes.

“My family and I have also stayed there overnight. It’s like spending a night in a museum. My daughter placed our sleeping pads right next to the sculptures. You fall asleep surrounded by magic, with the light from the street making everything shimmer with different colours. In the morning, you can’t figure out what kind of a strange place you woke up in.”

In summer, the foundation opened the courtyard of the workshop to the public, allowing visitors to view the display there. In autumn, the team hopes, the workshop will start functioning as a museum.

“We have been planning this for a long time. The war made us realize it’s time to finally do it. Volodymyr Melnichenko is a true national treasure. We are interviewing him about his and Ada’s life, describing and cataloguing the works and preparing for the opening of the museum.”

As part of its activities, the ESI Foundation supported Oleksandr Pipa, an icon of Ukrainian rock music scene who currently heads the Attraktor music duo and has also founded such bands as Borshch and VV.

We spoke to the musician about his activities as a volunteer and a music maker during the full-scale invasion.

“I live on the outskirts of Kyiv – my windows overlook Irpin and Bucha – so in the first two weeks I helped to build fortifications at the entrance to the city. Later, I joined territorial defence forces. As their member, I guarded a checkpoint on the highway leading to Irpin.

By coincidence, one of the guys in my territorial defence unit used to serve in the Berkut special police force. On February 18, 2014, when I was wounded on Instytutska street in Kyiv, he was also there, but on the other side of the barricades. Today, he is fighting at the front.

When active hostilities in the Kyiv region ended, I was transferred to the reserve.

However, I was unable to return to my habitual life. Now, my days go like this: I volunteer at night, fall asleep in the daytime, and in the evening, if I’m lucky, I work on some music.”

Attraktor is currently recording their cover of a song by The Ukrainians, a British band that composes and performs songs in Ukrainian, occasionally stylising them as folk songs. (The duo’s drummer played with The Ukrainians 30 years ago.) These days, the British band gives concerts in support of Ukraine and intends to release an album comprising covers of their compositions that have been created by Ukrainian groups.

“We are making a new recording of the song ‘Cherez Richku Cherez Hai’. The original is very good; our version just takes the song in a more radical direction. Recently, we’ve also recorded our take on an opera aria for a compilation of tracks by Ukrainian performers. This collection will be released by the American producer Danny Saber.”

As for his own music, Oleksandr says he wrote some songs in the spring, but shelved them for now, as he finds them too depressing. However, he continues his artistic quest.

“Music is an essential part of our lives nowadays. Personally, it helps me to stay in good shape. I also think that we are discovering new dimensions of music as art. Its beauty lies in its diversity and, we can add, its flexible nature. While it may take some artist 10 or 20 years to write a symphony that will reflect the events we are living through now, other musicians are already producing songs every day. Of course, both artistic responses are valuable.”

The Odesa Ship Repair Yard spent many years as an abandoned industrial building, a sight not uncommon in the post-Soviet space. Recently, however, the shipyard has been revitalised by artists who set up workshops on its territory and started working and living there.

On February 24, the artists lost access to their workshops, as the shipyard is located right next to the border zone of the port. After two weeks of volunteering in Odessa, they left for the west of the country, searching for shelter there. Eventually, though, the group realised that they were primarily looking for a studio rather than accommodation, since their goal was to return to work.

We talked to @xraketa, the project’s curator, about their Lviv hub Osrz4, which received support from our initiative.

“We really wanted to do the stuff we know, to be useful in our capacity as artists. At first, we were looking for a workshop in Chernivtsi, but on the way there we made a week-long stopover in Lviv. While there, we were taken to the industrial building known as the Red Building at 31 Zavodska Street and shown a former recording studio and the space we could use as a workshop there. We agreed to take the space. At first, we also stayed there overnight.

In Chernivtsi, we also rented a workshop, cowork_cv, complete with a sewing area and tools for wood and metal work. The workshop still functions, but no longer under our direction; it’s being turned into a co-working space.

The concept of our space is simple. If you want to create something, you are welcome to use our studio and tools. Incidentally, the tools come from the Odesa shipyard. Its management told us to leave everything behind, but we managed to get our instruments out. We were given barely one hour to pack. Thus, one could say that the tools have been rediscovered and started a new life here."

The workshop is undergoing renovation. To complete it, the curators work in shifts. The plan is to divide the space into several zones: a sewing room, separate rooms for small object and large objects production, a photo zone, a teletransfer corporation, a tattoo room, a showroom and a library. Each zone will be assigned a curator and provide enough space for 1-3 residents.

The studio space in Lviv has already been used by more than 10 artists whose art practice took different shapes: making sculptures and furniture, creating murals and cinema, setting up a hairdresser’s. The workshop is open to everyone.

In October, a DIY and experimental art festival is to take place in the studio space. The curators and participants of Undercover.residence, whose workshop is also supported by ESI, will hold masterclasses on linocut and printing on clothes. Guests can also expect a music program featuring sound performances – and much more.

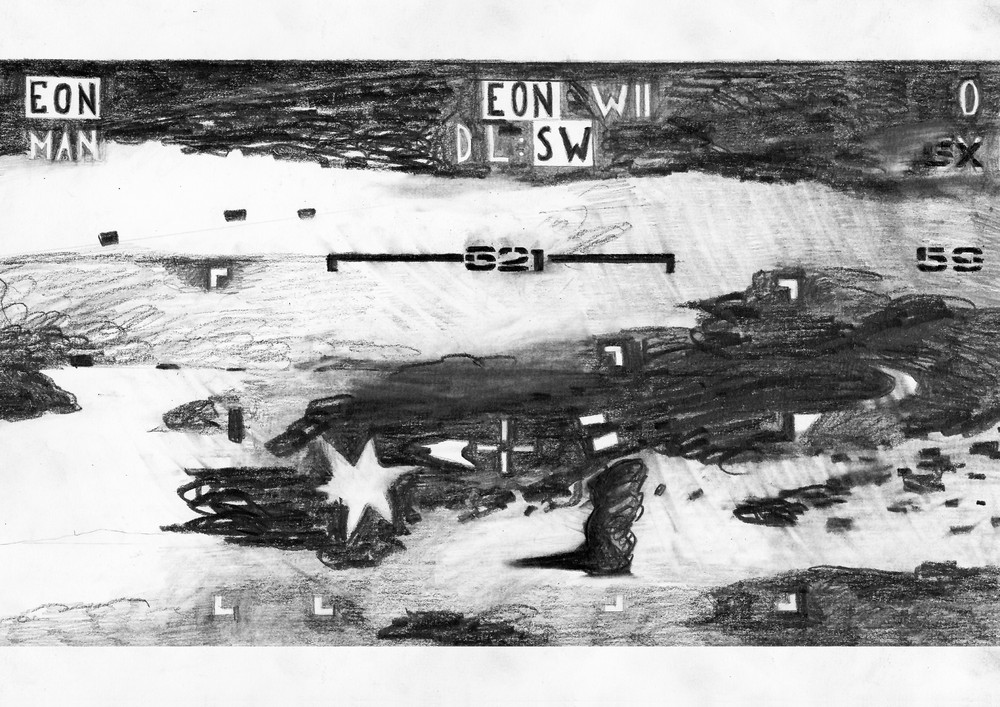

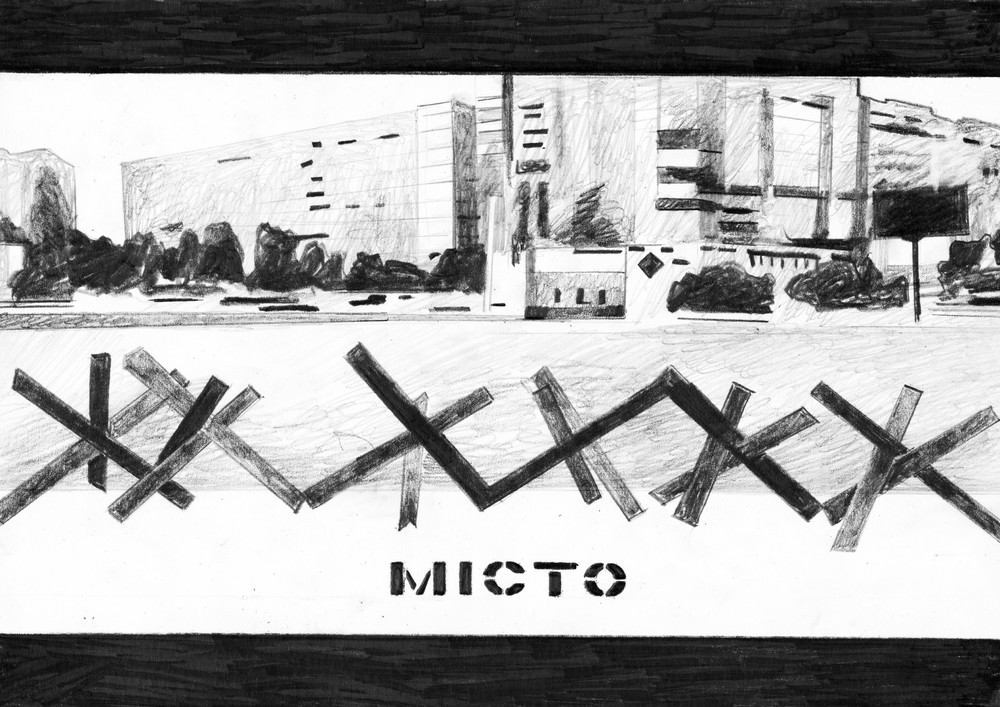

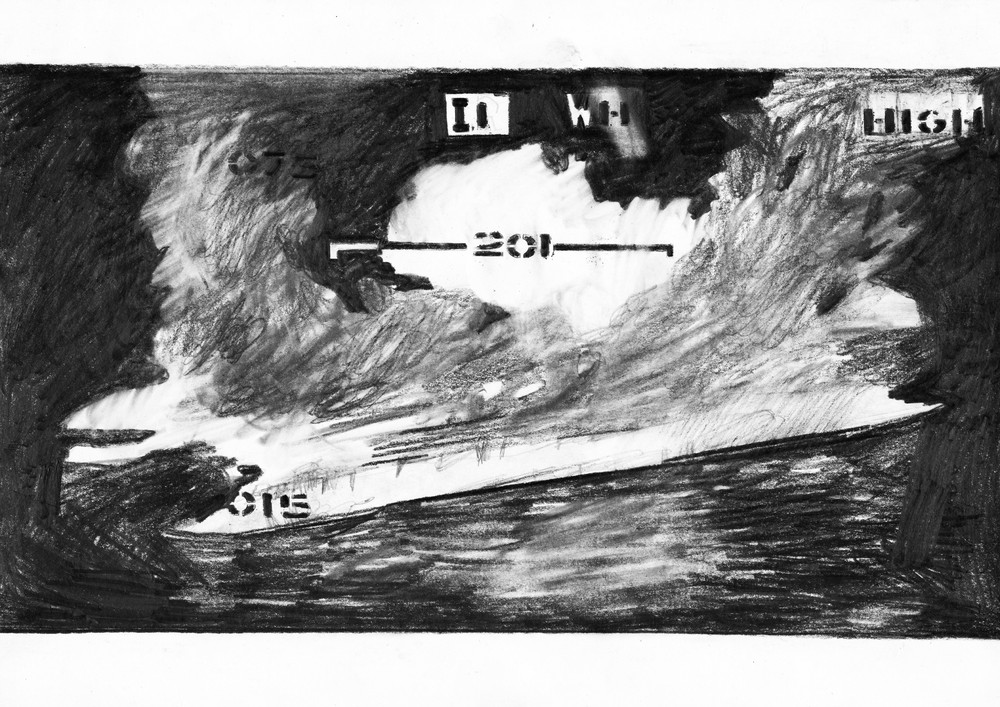

In his works, artist Vladyslav Riaboshtan, supported by our initiative, focuses on Ukraine’s industrial space. Using large canvases and a variety of painting and photography techniques, Vladyslav depicts subways, railways and industrial areas. After the invasion, he started working on the War Views series. Instead of canvases and paints, the artist resorted to A4 paper and black chalk. You can find the War Views works in the carousel.

Read on to find out more about the mobility of art in wartime and discover whether it is possible to work on old projects in the new reality.

On the eve of the invasion, Vladyslav was in Kyiv, working on a series dedicated to Kyiv subway. After February 24, he sheltered in that same underground for several nights. Later, the artist evacuated to his friends in Lutsk. While there, he began the War Views series.

"At first I was in a daze, constantly updating my news feed. I wanted to reflect on the events but had no idea how to do that. I was used to creating large canvases, and they were out of the question. If I had to leave or if Belarus attacked, I couldn’t take them with me. I didn't even have a suitcase, just a backpack.

Then it occurred to me I could use A4 sheets. It’s convenient: you can fold them and take them with you at any moment. And I always carry the 4B pencil in my pocket. I thought it was an appropriate combination: in those early days, our thoughts were also black and white: road dust, smoke above houses, early spring dirt against the backdrop of the white sky.

At first, my drawings centered on images from Bayraktars. They were the first thing that gave me hope of victory. Over time, more subjects appeared: military structures, destroyed buildings, anti-tank obstacles on city streets. This series deals with various aspects of the war, it’s a kind of personal diary. I think I will continue working on it until the end of the invasion."

War Views was exhibited in Poland and Austria, as well as in Kyiv, at Imagine point. In addition, an exhibition in Lviv is being planned.

For now, Vladyslav travels between Kyiv and his hometown of Dnipro. Upon returning to his workshop, the artist wants to recreate some of the works from his war series in a large format. He also means to finish the canvases dedicated to Kyiv subway.

"Before, I never saw the subway as a shelter, but spending several nights there made me look at its interiors and tunnels differently. I want to continue working on this series, searching for subjects and meanings from a new perspective."

On February 24, Pavlo was in Kyiv. Later, he left the city for the Khmelnytskyi region and then went to Lviv, where he stayed for several months. Meanwhile, Otel’ became a volunteer headquarters where Molotov cocktails were made, a logistics centre and a warehouse were set up and tactical training was conducted. Pavlo coordinated these activities remotely, invited foreign journalists and gave interviews.

When the Ukrainian army repelled the attack on Kyiv, Pavlo returned to the capital and relaunched Otel’ as a club.

“It’s like being Edward Scissorhands. What else can he do but give people haircuts and trim lawns? I decided to do what I do best: organise events and concerts. Conceptually, organisationally and financially speaking, we need to foster Ukrainian culture and unity.

Now, all our events have a common goal: raising money to support the Ukrainian military. For culture, having tangible impact is crucially important. We have recently had a Pozhezha (Fire) party showcasing a line-up of young indie artists who raised funds for tombstones commemorating fallen Ukrainian soldiers. These young performers can simply earn money for themselves but choose to collect it for causes like this. Instead of frightening, this inspires me. That’s the reality we currently inhabit.

Otel’ is more than just an entertainment establishment. It’s a space that affects culture, both directly and indirectly. Face-to-face contacts between people in this sphere matter a lot; in addition to increasing influence, they produce a unique charm. However, there are few venues in Kyiv where young performers can play, especially today.

After the beginning of the full-scale invasion, we have discovered that some Ukrainian performers cling to imperialistic values and lack civic mindedness. This has brought about a change in the music industry. Cancelling Russian culture means that many artists became irrelevant. While they are once more searching for their voice, new musicians have emerged and taken their place. They are creating music that reflects our current reality. It’s a pleasure to watch them. I want to help them, and that’s what we are trying to do.”

In 2008, together with engineer Maks Robotov, Lera started the SVITER art group project. After the beginning of the full-scale war, Max joined the army, while Lera continued artistic practice.

When the war started, Lera was in Kyiv, where she still lives and works at the moment, as she decided not to leave the city. Together with her husband, artist Ivan Svitlychnyi, they lived for a month at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, where their friend Oksana Barshynova worked, because the museum needed round-the-clock maintenance.

“It was an interesting experience. Apart from us, there were other employees who stayed in the museum at all times; we solved day-to-day tasks, spent nights in the bomb shelter, tried to watch movies and read the news endlessly”

The artist never stopped producing art. According to Lera, work has become a form of escapism and even therapy for her.

Polianskova is currently working on a project dedicated to the meme culture.

Back in April, while driving through Kyiv, Lera saw the delegation which included Zelenskyi and Johnson. She decided to give them two ceramic roosters which she happened to have with her in the car. A rooster like that survived in a ruined house in Borodianka and became a meme. The photo with Lera also went viral.

“I am delighted that I drew attention to Vasylkivka majolica and the art of the Protoriev family. It always pains me when I think of the Independence Square underground passage, its ceramics and mosaics. Although the place is a real treasure, it is in decline. I hope the newly found interest in this art means that after the victory there will be opportunities to preserve these fantastic works”

— Lera Polianskova, artist

“In many ways, our war is unprecedented; humorous communication and identification is one of its features, a manifestation of Ukrainian vitality we can take pride in. Fighting the enemy with the help of laughter is not a new thing, but, perhaps for the first time in history, it has become a truly national phenomenon. Patron the dog, the Madonna of Kyiv, Phoenix the cat, a jar of tomatoes, a rooster from Borodianka: they show us what we are fighting for, who we are and why we can and should continue to fight”

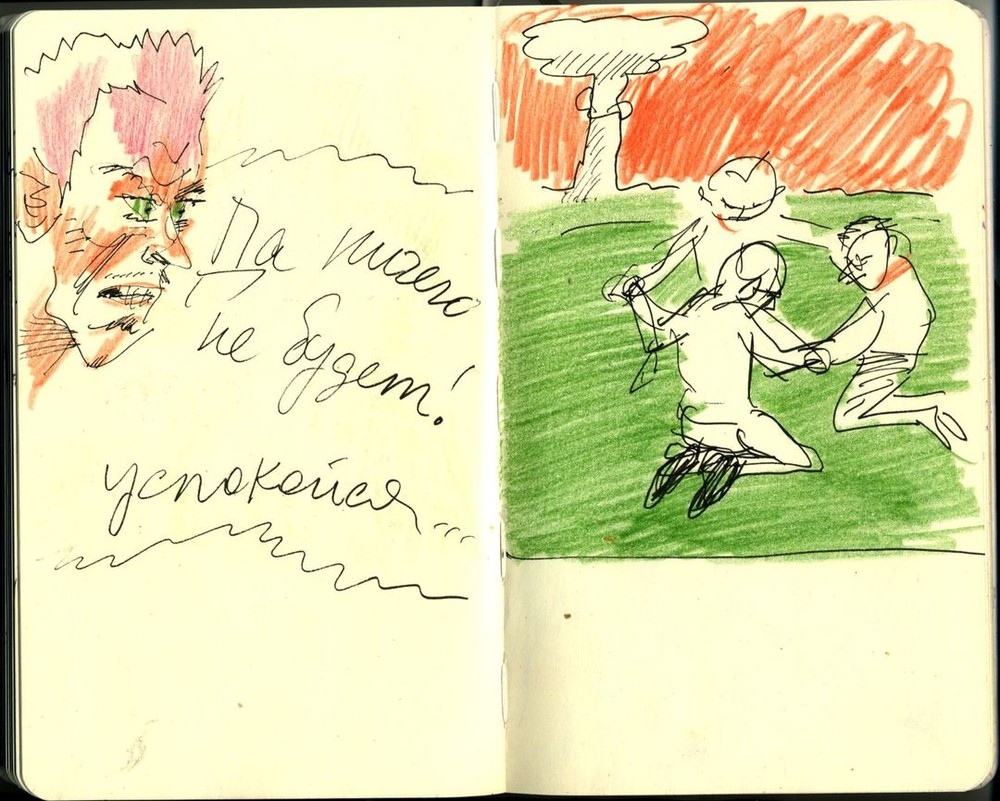

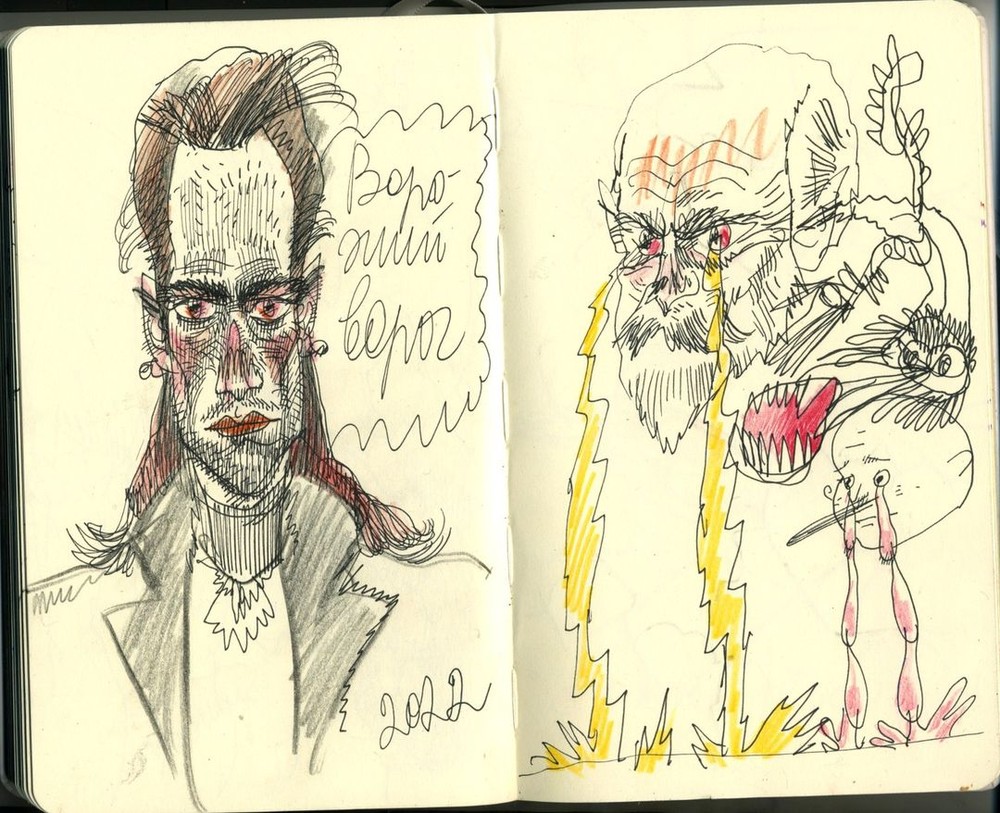

“I’ve been keeping a diary since about 2016. In it, I jot down important bits and pieces of information: passwords, dates, ideas; I also make sketches there. I always keep the notebook at hand. I don’t have a very good memory and I’m not terribly organized, so it helps me to remember things. Its functions haven’t changed after the start of the military invasion.

I learned about the start of the war on Facebook. Later, I heard the explosions myself; at the time, Katia and I (Anatolii Bielov is the guardian of Katia, his sister’s daughter, a minor) were in Troieshchyna district. Upon realizing there was nowhere to hide, as there is no bomb shelter in our house and the school nearby is not a reliable shelter either, we went to Lviv.

Our friends took us in for three months. I was in this constant state of limbo: the plan was to take the child abroad, but all options for leaving disappeared as quickly as they arose. To find a solution, we had to return to Kyiv.

Certificate of No Criminal Conviction and Certificate from a Psychiatrist were created in Lviv when I was going through bureaucratic torture to obtain custody of the child. The list of documents included these two certificates. Later it turned out, however, that I wasted time and money getting them: in my case, they were not needed. These sketches stand as a reminder of pointless efforts and bureaucracy.

All artists are different, as are their practices. Some react to the news quickly and reflect it in their art, making posters which inspire people to fight. Others, for now, are simply processing the events internally.

I have an idea I want to start working on later, when my daughter and I don’t have to live in survival mode. Currently, I am not an artist, just an ordinary Ukrainian citizen trying to save their child. I look at everything around me through the lens of art, though, which helps me to distance myself from stressful events to a certain extent, and not to lose my mind.”

At the time of publication, Anatolii has managed to take his daughter abroad.

Sana grew up in Odesa, but later moved to Canada. She returned to Ukraine in 2020. The war found Sana in Kyiv; the next day, she went to her grandmother who lives in a village in Odesa region. Sana stayed there for more than 3 months. Recently, she has returned to Kyiv.

“At my grandmother’s, I didn’t have enough space of my own. I set up my workshop in the shed. I had no work materials with me, so I had to experiment. I used wallpaper, wood, even a board for cutting up butchered pigs. I found it in the shed; my great-grandmother and great-grandfather made sausages.

I didn’t tell my grandmother that I took the board immediately after I did it, as she is unwilling to part with objects which have a history. In the end, though, she liked my work.

During my stay in the village, I created about 100 works. I tried to think beyond the difficult or unusual nature of the object acting as my ‘canvas’. As a rule, I didn’t endow the material itself with symbolism.

However, there is one work consisting of three separate boards: on one of them, a mother is depicted, the other two show her children. You can put the three pieces next to each other or separate them. This is quite symbolic, as families are being separated now due to deportations and deaths.

A month ago, I returned to Kyiv. Compared to the village, I noticed that it is harder for me to work here. In the city, I lose concentration; besides, I do not feel the war here. I don’t know whether that’s good or bad.

I used to avoid concrete images, but during the war I started using images carrying immediate meaning: our national emblem, bread. It also seems to me my previous works were lighter, more weightless. I want to return to that, to recollect how I painted before the war.

At the same time, I want to continue working with the symbols of grain and bread, to explore the theme of the sowing season and the problems that await the entire planet if the war does not stop.

I certainly do not judge people who have gone abroad, but personally, I find being in Ukraine more comfortable psychologically. I know that when I leave, I will feel torn from my usual context.”

“Photographing parties, I’ve always tried to show something profound: to capture displays of love and care. I loved Kyiv because it’s a city of opportunities where life happens at a faster pace than elsewhere, but for the last year and a half I’ve been yearning for more peace. I even considered moving to a quieter place, looked at such variants as Irpin and Bucha.

On the morning of February 24, I woke up to the sound of explosions in my home in Kyiv. I went online and saw that Putin has recorded a televised address. I was stunned: I have a cat and no pet carrier for it. So I took a bag with films, which I’d packed just in case a few days before the war (I’ve been using film in my photography for 12 years already), put my cat into a regular bag and left the house. My friend and I agreed to meet at the train station. He is a digger, so he knows his way around Kyiv’s underground tunnels. He said: if it comes to the worst, we can hide there.

We decided to check out one such “shelter” near Vokzalna metro station, but it was very damp. I remember us standing at the entrance: it’s gloomy, the sky is overcast, the only sound is that of a plane flying overhead. We didn’t know how to react to that. We wandered the streets for a few hours before eventually heading to a metro station where we stayed overnight. We were lucky that metro workers brought a carriage to the platform. We jumped inside, and it was less cold in there. After a few days of going from shelter to shelter my friends and I decided to evacuate. First, we arrived in Chernivtsi, but when we heard the air raid siren there, we chose to move to my friend’s family in Kryvyi Rih. It turned out to be much quieter there.

Before the war, I used to work as a stylist on sets; after the war began, my profession became irrelevant. I started volunteering as an artist: handed over some of my works to several foundations and organizations which sell art objects in the form of NFTs and donate profits to charities helping Ukraine. A few of my works sold out for charity, but I only managed to sell one piece to support myself.

Several days ago I returned to Kyiv. Walking from the train station felt chilling, exactly like it did on February 24. Perhaps I just need some time to adapt. The war made me look differently at myself and my environment. Now I take it one day — no actually, every hour — at a time, because I don’t know what to expect.”

Yevhenii Arlov is a participant of the Ivano-Frankivsk “Working Room”.

Read on to find out how the war changed Yevgenii’s life and what he is working on within the residency.

“On the morning of February 24, my girlfriend and I were at home in Kyiv. Her mother called her and said the war had begun. We stayed in Kyiv for the first 10 days; our friends joined us, so there were six of us. We tried to be useful, preparing Molotov cocktails and getting food to the members of the local defence forces.

On the 1st of March I thought we should send the girls to Ivano-Frankivsk. There was a terrible crush at the station, everyone wanted to get onto the train. We had to push away men who tried to board before women. I saw a woman sitting by the train and crying. I asked her what happened; she said she was the conductor, pushed out of the carriage. Eventually, the girls managed to board. The boys and I stayed behind. We stayed in the city for five more days, but managed to leave after the railway station was hit – the train was almost empty.

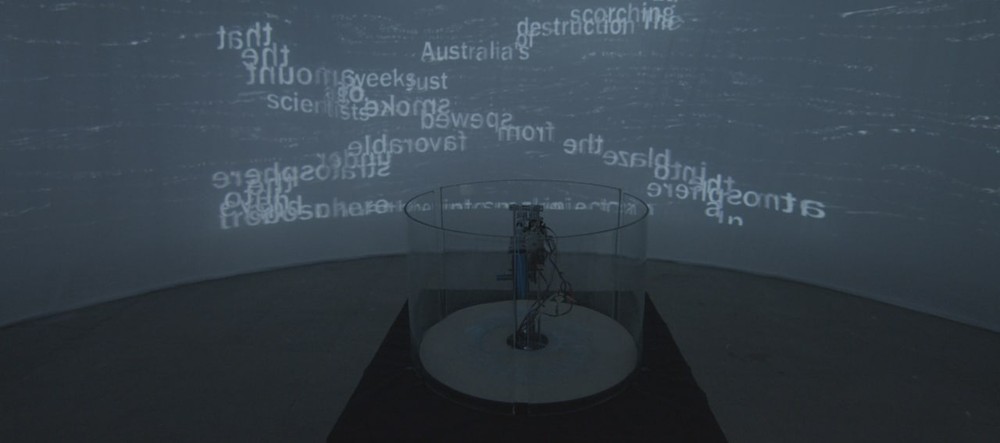

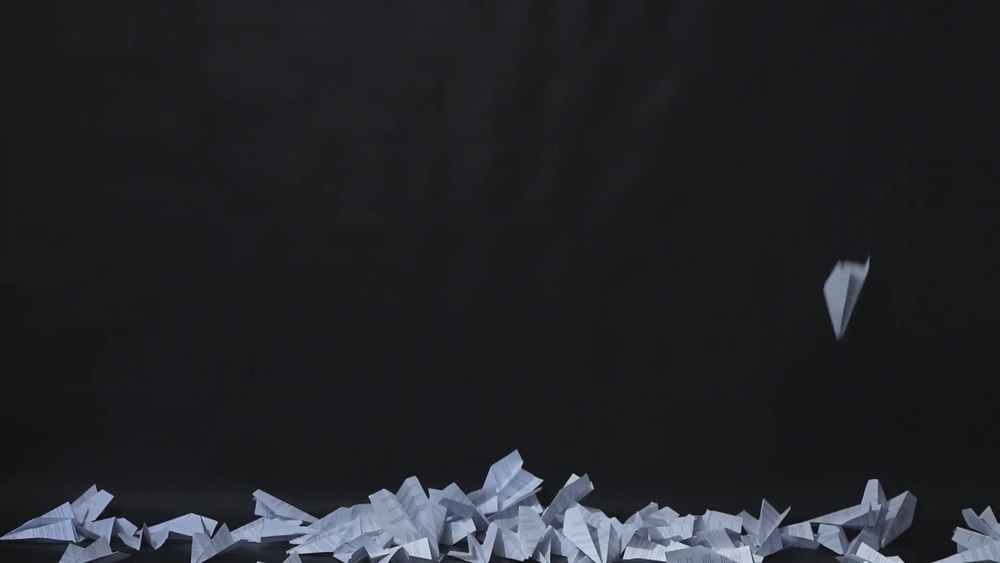

These days, art helps me to stay afloat and in touch with reality. It’s impossible now to work with themes that have nothing to do with the war. I came up with an idea for a performance based on the Budapest Memorandum of 1994. This document is a prime example of political games surrounding Ukraine as a subject, conducted by global players. The guarantee of sovereignty turned out to be nothing but words.

In a manner reminiscent of the Budapest Gambit in chess, Ukraine relinquished its nuclear potential and part of its armaments by signing the Memorandum to gain a better position on the world stage. Violation of the rules and the very fact that the game was created comprise the culmination of the international relations system. The deconstructed text of the Memorandum is transformed into poetry contrasting with the context of the original document. On a physical level, the document turns into a chessboard with figures.”

The story of the designer and artist Nastia Teor. Read on to find out how the war changed her life.

“On February 24, I was asleep in my home in Kyiv’s Lukianivka district. My neighbour woke me up. I don’t remember whether I started crying immediately or later, but I definitely was in shock. Soon, my neighbour left; I was alone in the apartment and did not know what to do. However, I was convinced that I had to stay in Kyiv and defend my city. Of course, in reality I was unable to defend it from either soldiers or missiles, but it seemed that my presence was important. It seemed that leaving the city would amount to a surrender.

I packed my bags, watered plants and went to my parents, who live in Kyiv as well. On the second day of war, I started looking for ways to help others. My partner and I started raising money to buy medicines and food for the cadets and elderly women. My mother cooked hot meals, and we distributed them to people sheltering in the underground. My parents continue this volunteer work, while I moved to my friends’ place, also in Kyiv, and switched to art activities and online volunteering.

Before the war, I worked as a designer and artist. War meant automatic cancellation of all my projects. Then I got the idea for the artwork A T T E N T I O N ! Air raid sirens! This work constantly changes, reflecting the events of the war and the development of my views. It became a sort of a diary, a historical testimony and a way to find a place for art in the war. I use the air siren as a material that helps to convey sensory experience. Since the first day, the siren became a part of my body. My life adheres to its rhythm: when the siren is off, I’m free to move; when it’s on, I go to the corridor. Today, this sensory experience is probably extremely familiar to most people in Ukraine but completely unfamiliar to people in the West. Therefore, one of the goals of this work is to bring us closer, at least marginally, despite the abyss between us.”

What Am I Doing Here? is a new track by musician Mariana Klochko, whom we were able to support within the framework of our initiative. Before the war, Mariana lived in Kyiv. Among other things, she has worked on the soundtrack to the Ukrainian film Stop- Zemlia. We asked Mariana whether she can work during the war and how she sees the place of music in current circumstances. What follows is her response.

“With music, there has been no division into ‘before’ and ‘after’ the start of the war for me, because music is always by my side. That said, there was a pause in my work because of by the events in our country, but fortunately it did not last long. Now I’m writing a lot, preparing a big release, which means a lot of work, but for me it’s a lifeline. I do not write music about the war; I cannot sing about these terrible events. Rather, I see this material as therapeutic.

I worked a lot on the piece I’m now sharing in the last days before the invasion and then a bit in early spring. At first, it was a very minimalist composition, but later it acquired layers of additional elements. The title poses a question: “What am I doing here?”. This piece is my manifesto of confusion: not the kind that slows you down, but the kind that gives you strength.

I think the attitude of many people to music changed because of the war. On the one hand, music, and song in particular, is a very powerful instrument which can lift your spirits; on the other hand, how can you listen to it calmly after you have at least once heard the sounds of explosions or sirens? Our hearing is more exposed now, and we started listening in a different way. It seems to me that this is a big challenge for musicians: you run the risk of becoming a nuisance, almost, so you must be very careful what you do.

I think it is important now to be doing something that helps you to keep your head and (or) can benefit others. If it’s music, great, if it’s some other activity, wonderful.”

The story of the artist and tattooist Marianna Tarish from Kherson. So far, she remains in the occupied city.

“My mom woke me up at 6 a.m. on February 24 and calmly said the war had started. The first days were very loud and dangerous. I still remember a missile flying over our house; I went out onto the balcony and, for the first time ever, felt the smell of gunpowder. To cope with it all mentally, my mother and I began to clean the entire house: wash the windows, tape them up.

I've been creating paintings and graphics, illustrating books, decorating facades and making artistic tattoos for 10 years. During the first few weeks of the war, I could not work at all. It was awful — you sleep in the corridor on a mattress, scared that something might hit you. But then I reconciled myself to the inevitability of it all, and things started to come together.

Now, I am working on war-themed drawings. The work is very difficult, but also very interesting. Living through the actual events and hearing people’s stories motivates you to create. At the moment, earning money is impossible, as tattoos are not in demand, and nobody is buying paintings, either; people don’t even have money for food. Survival is only possible thanks to foundations.

We have been living amid silent terror for two months. So far, I haven’t tried to get out of the city; it’s too scary. I’m afraid to leave my mom, who categorically refused to go anywhere. I’m scared because I’ve heard many stories about people who tried to leave the city and came under fire. I’m scared of meeting Russians or Kadyrov troops, who control the checkpoints, face to face. Besides, it is very difficult to leave if you have no car. Drivers taking people from Kherson to Mykolaiv charge people $400, and there are no official evacuation corridors.

I’m living one day at a time, trying to enjoy simple things. Horrible as it sounds, I’m getting used to fighting. I can now smoke during explosions, even while the blast wave makes the glass shake. That said, I also have a packed backpack at hand, as I don’t know what we can expect when our army starts taking Kherson back. We are all of us really looking forward to that, but, on the other hand, we are scared: we realise it will not happen quietly, Russians will not renounce control without a fight.”

Anton Rieznikov is a Kharkiv artist and illustrator whom we managed to support within the framework of our initiative. When the war started, Anton was in Kharkiv, where he stayed for several weeks before moving to Lviv.

In Kharkiv, Anton, his friends and girlfriend had to shelter in art studios located in the central district. “We hid in a basement, but after a while it became unbearable. And not only because of loud explosions, but also because of the growing tension inside the team. We had to make a choice and decided to go,” Anton says. However, because of the crowd and panic at the railway station, they only managed to leave the city on the second try.

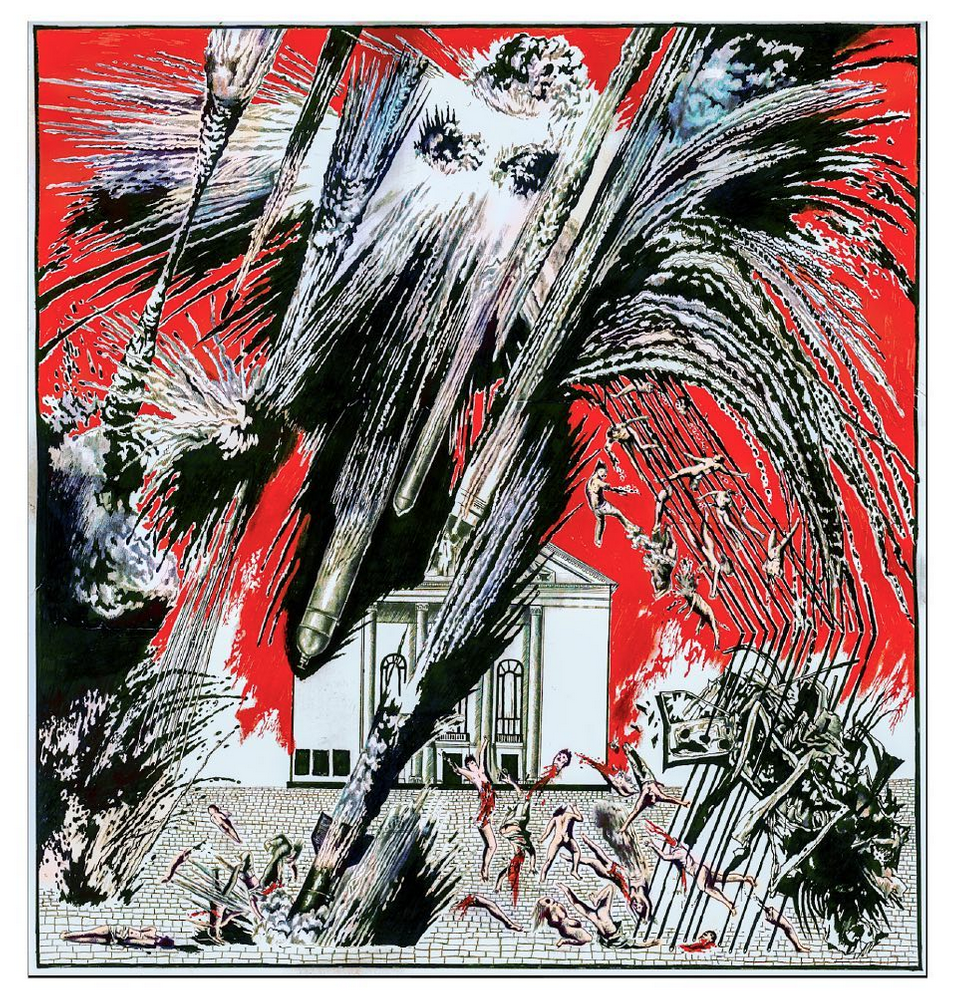

The works we present were created by Anton for the Meta history project, an NFT museum which publishes artworks exploring the war theme; the proceeds are donated to foundations supporting Ukraine.

The work Theatre of Combat was shown at the Piazza Ucraina exhibition during the Venice Biennale. “At the time of its creation, I was reading Lovecraft and decided to depict an explosion as a space creature devouring people and destroying everything in its path. In fact, it’s a personalization of explosion as Lovecraftian horror,” Anton says.

In another work, “Landscape, 2022”, Anton tried to rethink the traumatic nature of military experience. “The idea behind this work is that someone who has survived the horrors of war sees them everywhere. Even in idealistic landscapes such a person imagines deaths, wounds and destruction,” to quote the artist.

Anton continues to work but believes that art is currently powerless to emotionally convey or amplify the horrors of war felt by Ukrainians these days. “It seems to me that interesting developments may arise after the war, when we start rethinking everything that happened,” Anton says.

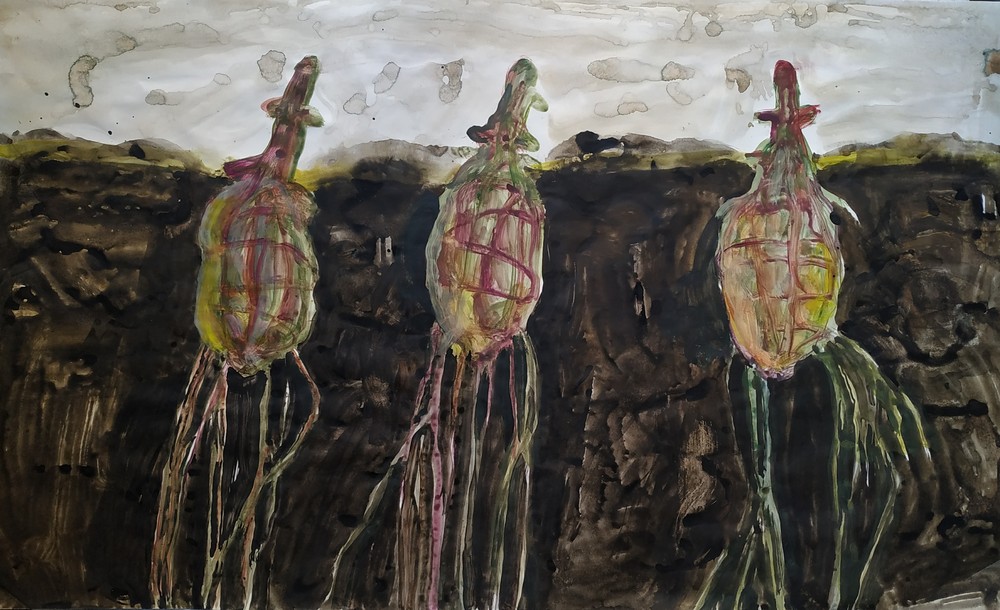

In addition to personal financial assistance, our foundation also supports cultural residencies in Ukraine. One of them is the Ivano-Frankivsk residency “Working Room”, created on the basis of the “Asortymentna Kimnata” gallery. Today, we will tell you about Katia Aliinyk, a participant of the residency. Katia was born in Luhansk and this year became an internally displaced person for the second time in her life already.

“In 2014, when the war in Donbass began, I was 15. My family and I lived under shelling for a month. We spent a lot of time in the vegetable garden, watering tomatoes under bombing. Mom took my sister and me away to safety on the last train; after that, railway service was cut off.

I thought I would find it easier to survive a full-scale war than those who never had a similar experience, but no. I am happy that I was able to relocate from Kyiv to Ivano-Frankivsk, where I am able to work. It was very important for me to stay in Ukraine.

Back in September 2021, I started working on a series of paintings in which I reinterpreted the theme of the occupied Donbass. I did not resort to images of immediate military nature: I painted nature, plants, soil. I thought a lot about such weak gestures of resistance as hard work on small private plots of land on the occupied territories, those last patches of land where people feel in control of their lives. I drew grenade-shaped, munition-like roots. They have been in the ground for a long time, have even grown some sprouts and now have healing properties: they can cure political blindness or restore one’s voice.

For Ukrainians, their whole life changed after February 24. My art has changed as well. Before, I noticed that people passively observed events; now, I see mass solidarity and resistance. I continue working with earth as a theme but bring my work up to date to reflect current events. I am considering the less obvious consequences of the war which we will notice later, like toxic liquids seeping into the soil because of hostilities.

These days, art is reactive rather than reflexive. However, after the war it will serve as an important artifact: as evidence of personal sensory experience of these events.

Projects

Asortymentna kimnata

Kyiv Biennial fund (ESI) has launched support for art residencies in Ukraine hosting artists that have been forced to flee their homes. At this moment we were able to support two outstanding initiatives: art laboratory “Robocha kimnata [The working room]” based in Ivano-Frankivsk and Na poshti residency [At the post office] in Ternopil.

“Asortymentna kimnata” together with Kiyv-based curator Lesya Khomenko has launched an art lab “Robocha kimnata”. Its idea is to create a fast-tracked residency format for displaced artists based in existing “Asortynemtna kimnata” facilities. The artists Sasha Kurmaz, Kateryna Aliynyk, Taїra Umarova, Yaroslava Khomenko, Yevhen Arlov, Nikita Kadan have now joined the lab.

Creative cluster Na poshti founded in 2021 in Ternopil has a goal of supporting contemporary Ukrainian culture. Since the first days of the war, it began accepting involuntarily displaced persons offering a shelter to 30-40 people on a daily basis. The residency was established to welcome artists of all strands of contemporary art coming from the Eastern regions of Ukraine that suffered the consequences of the ongoing war.

Sorry No Rooms Available

Uzhhorod residency Sorry No Rooms Available is one of the projects we were able to support within the framework of the ESI. Since the beginning of the war, the residency has been hosting artists from the regions of Ukraine where hostilities are taking place. We talked to the residency coordinator Petro Riaska and two of its participants about their work there and how they see the place of art during war.

“Currently, we have five participants living in four rooms. Artists can stay at the residency for up to two months. We host artists who at the moment are in urgent need of shelter, but participation in the residency presupposes creating an art product. At the same time, we cannot compel artists to reflect on the theme of war in their works; presently, this process may prove too painful for some.

Art can help, because art can be seen as a component of culture, and culture as a component of the country’s economy in general. And culture is something we are defending at the front, after all.”

Petro Riaska,

residency coordinator

“In my opinion, art retains an important role, since art is the language informing cultural codes through which we actualise our inner state when dealing with changing external circumstances, reality, time. With existence and nothingness.

At the residency, I am working on an online radio which will feature sound performances, fairy tales, audio collages. The goal of this project is to create a space of peace and emotional relaxation absent from our current media flow. Having such a space is a must because we all need some ‘time-outs’.”

Oleksandr Yeltsyn,

residency participant, sound artist

“Art is vital, since art is also a kind of weapon, protection, symbol. To create worlds, you ought to have a sense of purpose and strength, and besides, people need hope. Art should ask questions, unite, help to create a connection between people: those protecting the country and those away from the frontline. For many, art and poetry are a means of salvation.

On the other hand, my artist friends often say that it seems like everything they have been doing lost its significance during wartime. Personally, I asked myself whether it was worth continuing to create and release works and concluded that the art world lives on, whether you participate in it (as an artist or as an observer) or not. I continue my practice; at present, I am preparing a series of albums, the first of which will feature militaristic sur techno.”

Oleksii Konopelko

Residency participant, sound artist

TU Mariupol Platform

The TU Mariupol Platform is an art space for young people in Mariupol. Its main mission is to promote human rights and freedom through art and develop critical thinking in Ukrainian society.

As part of the ESI Foundation activities, we have supported the founder of the platform, Diana Berg.

We spoke to Diana about Mariupol, memory and creating new safe spaces for youth from the East of Ukraine.

The team behind TU! and its art cluster OS worked on site-specific projects related to Mariupol.

"Mariupol is a city of freedom and resistance. Already in 2014, at the time of the first invasion, it rallied and repulsed Russian troops. There, you are on the edge of where Ukraine begins, where Europe begins. All around you, there is sea and the Donetsk steppe”.

After the invasion, the space where TU! was based served as a shelter for people who lived nearby. Now, it the space is controlled by the occupation authorities and there is no information about it.

“We try not to lose our connection to the city, so we talk about it and support people from Mariupol, wherever they are now. Eventually, we will return there. That is why we created the "Memoriupol" project where we collect memories of local residents and visitors as well as photos, videos, stories about the city.

Creating the project took longer than we expected. It turned out we had to wait a little bit: memories sting because of the recency of the events. However, we will present the project to the public soon”.

TU! and OS are also engaged in other projects, like the NUMO series of educational events during which female artists taught young people how to create viral content in support of Ukraine. Now the team is working on the rehabilitation and adaptation project “Trymaimos” (“Let’s Carry On”).

"Through our projects, we are trying to create a new safe space for young people from Eastern Ukraine. Because it is impossible to do that in the real world, as people are located in different parts of Ukraine and around the globe, we are building this community on Instagram”.

TU! also participates in festivals abroad and cooperates with international organizations. Together with Vitsche Berlin, the team is working on a media campaign debunking myths about Ukraine, pacifism and the USSR in Germany.

We asked Diana about the three places in Mariupol she would most like to return to:

The TU! space. My apartment. And the place on the seaside with the bridge over the railway tracks. You can see the plant, the sea, the railway station, and below, the old trains that used to run between Mariupol and Donetsk. It's the most beautiful place”.

Sophia Gerasymova's documentary project "Cognition Trilogy"

The film is divided into three parts: 'Separation', 'Running', and 'Donetsk is us, we are Donetsk'. It explores Sophia's personal experiences during the first wave of the 2020 pandemic and the period in 2014 when Donetsk was occupied by pro-Russian terrorists, causing Sophia to become a temporarily displaced person. In 2020, Sophia once again faces the loss of her home, separated from loved ones, and was unable to reunite with family from the occupied territories.

In 2021, Sophia and two artists from Donetsk launched the INAKSHE art project, where they create audio-visual performances in abandoned buildings destroyed by war. Sophia’s latest works also include the debut full-length documentary "The Diary of the Bride of Christ" by Marta Smerechynska, which premiered at the 28th Sarajevo Film Festival.

THICKETS, GROVES, WOODS AND BUSHES

Thickets, Groves, Woods and Bushes (UKR: Хащі, Рощі, Зарощі і Кущі) was a recent apartment exhibition in Kyiv curated by Oleksandra Pogrebnyak. The exhibition opened on February 24th, marking the first anniversary of Russia's full-scale military invasion of Ukraine and becoming a symbol of national resistance. For Oleksandra, this date also holds personal significance as it is her birthday.

The exhibition explores the experience of living in Ukraine during this long year and despite changing circumstances. It shares the stories of individuals, families, and communities, revealing their twists and turns connected to the war. Some of the artworks observe the landscapes that are inaccessible due to occupation when others focus on the liberated lands that have become territory of trauma and destruction. Another important line in the exhibition is the reclamation of voice through singing and humming which symbolizes the restoration of control and sense of belonging after a period of silence and restraint. By unveiling the lines from the title, one can discover the narrative aimed at highlighting the complex relationships between humans and other species in the natural world or built environment, and the ways in which art can foster a deeper understanding of the possible ways of coexistence.

Thickets, Groves, Woods and Bushes was inspired by ecological rejuvenation and featured Ukrainian and international artists who shared stories about the poetics of life and space, anxieties about an undefined future, and resistance as an integral part of life in Ukraine. The exhibition celebrated the resilience of the human spirit and its capacity to find hope and renewal in difficult circumstances.

Participating artists: Francis Alÿs, Yevgenia Belorusets, Alevtina Kakhidze, Roman Khimei, Dariia Kuzmych, Larion Lozovoy, Daniil Revkovskiy and Andriy Rachinskiy, Anton Saienko, Andrėja Šaltytė and Leopold Tax, Sana Shahmuradova, Svitlana Ulianova and Oleksandr Ulianov (from the installation of Prykarpattian Theater), Trevor Yeung, Anna Zvyagintseva, as well as the team of the musical (Tomas Hazslinszky, Myro Klochko, Katya Libkind, Ira Loskot, Larion Lozovy, Olga Marusyn, Oleksiy Min'ko, Olena Mordyk, Oleksandr Pylypenko, Volodymyr Pylyprenko, Dmytro Silny, Dmytro Tkalenko, Tamara Tkalenko, Tonya Zelenina) and Dmytro Chepurnyi with the text Landscape After The Battle.

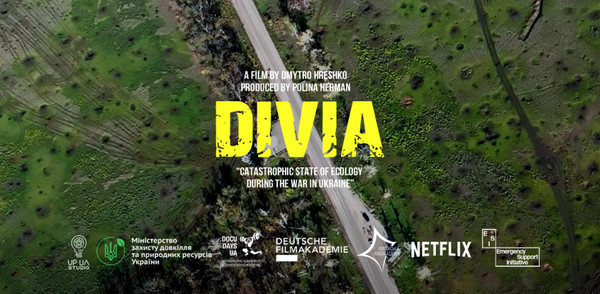

Divia documentary

A documentary film about the catastrophic impact of the Russian war on the ecological state of nature in Ukraine. It is a journey from the harmonious life of nature, to the fiery whirlwind of war, which burns the earth, forests and all living things. With the arrival of spring, nature recovers and brings new life among animals, despite the irreparable destruction. But the infinite scale of the tragedy does not give hope for a quick restoration of nature and cleaning it from the remnants of war.

Director Dmytro Hreshko

Producer Polina Herman/UP UA Studio

Associate Producers Andrii Lytvynenko and Viktor Shevchenko

Editing Mykola Bazarkin

Sound Designer Vasyl Yavtushenko/4Ears Sound Production

Music Mykola Makieiev/Horizon Music Studio

Color Marina Tkachenko

Film by Alina Horlova

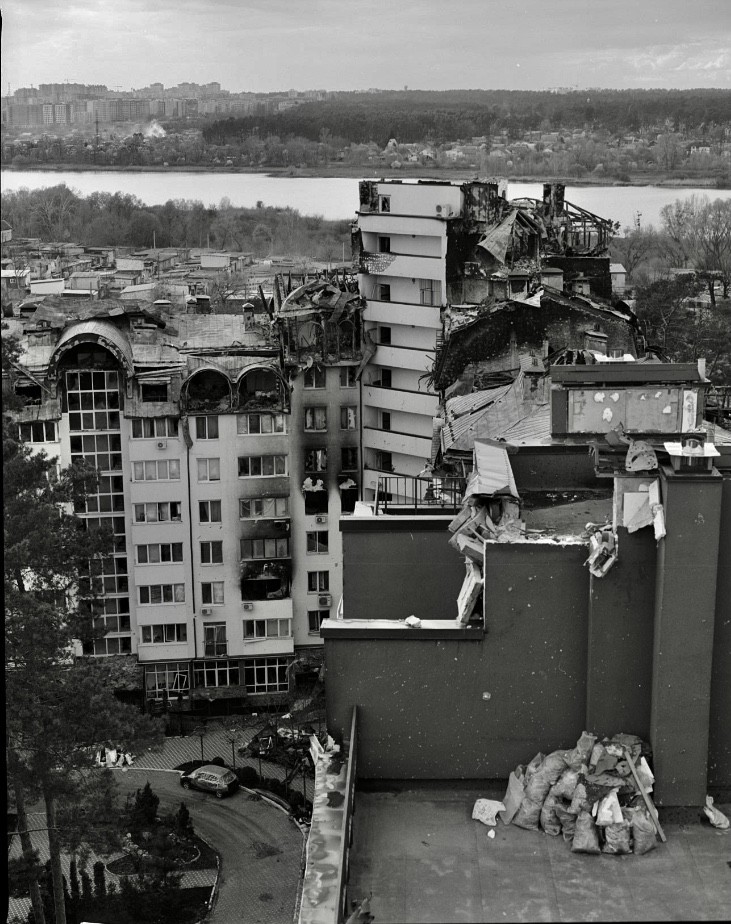

Within the framework of activities carried out by the ESI Foundation, we are supporting a new project of the Ukrainian director Alina Horlova. She documented life in Kyiv after February 24 and expanded her documentation work to the Kyiv region after the end of major hostilities there.

“In the Kyiv region, I filmed destroyed cities, bombed-out buildings, factories and farms damaged by shelling, people killed by Russian soldiers. I also documented trials of Russian war criminals”.

“Drawing on my previous experience, I would like to create a film about the current situation in Ukraine. Cinema should reflect Ukrainian directors’ perspective on this war", says Alina.

In her previous films, Alina has examined the consequences of the war by portraying war veterans and those who witnessed hostilities. Thus, No Obvious Signs (2018) focuses on Oksana Yakubova, a member of the armed forces who returns from the combat zone, and her path to rehabilitation. Similarly, This Rain Will Never Stop (2020) relates the story of the 20-year-old Andrii Suleiman and his family: having fled to Ukraine from the war in Syria, they end up caught in the middle of the warzone again. At IDFA, the largest documentary films festival, This Rain Will Never Stop won the award for the best debut.

War signboards

Urban visual space consists of multi-layered cultural and historical codes. Today, they are being mercilessly destroyed and altered by war. For the past ten years, artist Andrey Rachinskiy has been exploring one of these codes and creating an archive of signs found around Kharkiv. With support from ESI, Andrii is working on a documentary about Kharkiv, its people and the war seen through the lens of urban lettering.

On his page, Andrii publishes parts of his archive as well as photos of signs, ads and car stickers he sees on the streets of Lviv, Kharkiv and Kyiv. In an interview with Bird in Flight the artist noted that this visual diversity also attracts him with its absurd quality; it’s an opportunity to delve into Ukrainian subconsciousness, to examine the unofficial culture and identity.

“I have always been interested in urban space and lettering, especially in old signs: the multiplicity of shapes and letters, the variety of methods and options for their production. I have gathered a large thematic collection that includes my own photos, materials from archives, city guides and albums dedicated to Kharkiv as well as photos taken by tourists who visited the city.

After February 24, when I resumed working with this material, I realized that my major focus should be on documenting Kharkiv signs, both old and new, that are damaged by the war and the Russian invaders.

Every day, Kharkiv and the Kharkiv region come under Russian shelling. People die, residential buildings, schools, kindergartens, power stations, heat and power plants and other infrastructure facilities vital for the city and the region are being destroyed.

I believe it is necessary to record and preserve this history today. To create a film documenting the war and its consequences, reflected not only in the images of ruined lives and destroyed houses, but also in a more specialized topic: urban lettering”.

Art4Ukr

Solidarity, community and togetherness: A talk with Art4Ukraine about a fundraiser for artists in war

Art4Ukraine is a non-commercial and independent collective created by artists in Norway that raises money for humanitarian aid for the cultural workers in Ukraine with Kyiv Biennial. They auction art and organize offline events in Oslo.

We talked with the curators Lea Ye Gyoung, Anastina Eyjólfsdóttir and Io Sivertsen about their initiative and the newfound solidarity in the art scene.

The idea and the beginning of the project

Art4Ukraine started out as a single artist's idea to make an auction of Norwegian art and send money directly to Ukrainian artists. Jakub Baloun contacted his colleagues to see if anybody would donate their works for an auction. Anastina came in to help him reach out to artists and eventually brought Lea and Io.

Anastina: This project felt like a necessity because as an artist you don’t really have many financial resources to donate money. However, we saw an opportunity to create a different way for us to help Ukrainian artists through our works and practices.

The organizational process was very improvised in the beginning. We asked our friends to donate the works, and they spread the word and very soon, we ended up with 88 artworks to auction.

Lea: I think that's what a lot of artists actually needed but weren’t able to put into action. And our job was just to link them so they could contribute in their own way. I myself volunteered in Oslo apart from that but still felt alienated; this project showed me the way to artists’ solidarity which I care about and find extremely important.

Anastina: Because it was an emergency initiative, it would feel very wrong to be excluding any artworks in the process. Taste is a very subjective matter, and it felt impossible to create criterias for a charity project, so we welcomed any donation. The collection we ended up with was of different media as well as different levels of artists: famous professionals, young emerging artists and less experienced contributors.

The first exhibition at Kunstplass gallery

After gathering up works, Anastina, Jakob and Lea decided to make an exhibition in Oslo.

Io: It was essential for us to create a physical exhibition in addition to the online auction.

We wanted to bring people together, to create a meeting point where the audience could see the artworks, talk to each other, listen to music and take part in political gatherings. It also meant we could invite both local and international artists to participate in the creation of the program for exhibition.

It was important to be able to hang the works! It was so interesting to see how the donated artworks created a new meaning when they were hanging next to each other. In a physical room you have the possibility to juxtapose images and create new context, whereas online, the artworks just become a scroll.

The first show took place on the 12th of May at Kunstplass Contemporary Art [Oslo]. A gallery run by Henriette Stensdal and Vibeke Hermanrud. Kunstplass aims to Interact in public with queer, feminism and political themes. The curator and artist at Kunstplass Joanna Chia-yu Lin helped us to set up the auction.

Lea: We learned from the first exhibition that it's hard to organize the exhibition with large amount of artist with no funding as well as set it up. Everything costs money, even printing a poster or presenting the work well.

We decided to contact businesses and institutions in the local community and were very lucky to get sponsored by them. This way, for instance, we got to frame almost 15 works with professional-class quality frames by Artifix. A local record shop Råkk & Rålls sponsored post holders, and an architecture school (AHO) helped us build the wall for the exhibition. A lot of artists voluntarily came to help us set up.

PHOTOS FROM THE EXHIBITION

Kunstplass required a programme for the exhibition day so that the cause is spoken about in a more powerful and impactful way. Lea says they remembered a commercial on Instagram of a Ukrainian cine movement called Freefilmers who wanted to organise screenings abroad to raise money and support filmmakers in the country.

Freefilmers is an NGO from Mariupol, Ukraine, which focuses its films on human life and the struggle for equality and freedom while promoting independent filmmaking and grassroots initiatives in political arts and resisting colonial policies, imperialism, capitalism and patriarchy. Their main purpose now is supporting underground Ukrainian artists.

Lea: I really enjoyed watching the films by the Freefilmers. They are political, funky and experimental, and it was very hard to pick 5 for the exhibition. All the donations from the auction went to the ESI foundation by Kyiv Biennial; on the day of the exhibition, there were Ukrainian-inspired drinks sold, and all the profit was sent to the Freefilmers.

Art as expression: an exhibition at Nobel Peace Center

In the first round of the auction at Kunstplass Art4Ukraine, collected 68,000 Norwegian kroner. Soon after the first project, they were contacted by Nobel Peace Center in Oslo.

Nobel Peace Center were organizing the Freedom of Expression festival that followed an annual peace conference with Nobel Peace Prize winners and offered the initiative to make an exhibition and a relevant program of events there.

Io: When the Nobel Peace Center reached out, the war had been going for some time, and the immediacy of the crisis had slowly faded from the media and from people's minds.

So this was a great opportunity to arrange an art auction to remind people that the war in Ukraine was still going on.

The exhibition called Art as Expression opened on the 18th of August and the show's ending was on the 3rd of September. Io, Lea and Anastina had more time where they could organize themselves and work with different artists.

From the beginning, Art4Ukraine was supposed to be a Norwegian artists’ initiative, but soon they received messages from people worldwide and decided to take them in too. There were artworks from Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Brazil, India, Pakistan, Germany, Iran, South Korea, China, America, Canada, Denmark and Britain.

The most special features of the exhibition were artworks by ten Ukrainian artists made during the war. Due to the difficulties with shipment from Ukraine, the Ukrainian artists were asked to photograph the work and send it digitally, for it to be printed and framed in Oslo.

Io: When we received the works from the Ukrainian artists, it was like receiving a small window to a completely different world. And all of them were just so powerful.

We were all so humbled by being able to show them at the Nobel Peace Center, and it created a very compelling exchange between art, activism, storytelling and audience. In addition I think the Nobel Peace Centres festival managed to create a great framework for our exhibition. Because their program reflected many of the themes in the works we were showing. It put an emphasis on why culture and art is significant in society, but also for everyone living in that society. Artists are the storytellers of our times, and culture is a conversation we all should be able to take part in.

During the exhibition we were approached by many different people who wanted a tour around the space and wanted to hear the stories of the artworks. And especially of the Ukrainian artist. So I felt many different layers of conversations were being made, we had the personal stories of someone seeing their homes being burnt, but also more global discussion around freedom of speech and why art and culture is still important in times of war.

There were also different programmed events during the exhibition: poetry readings, artist talks and performances, most of them focused on Ukrainian art and literature.

Anastina: Even though I studied in the Netherlands and there was a big international community, I knew very little of the Ukrainian art scene. I would expect it to be more traditional, the exhibtion became an interesting opportunity for us and all the visitors to explore Ukrainian contemporary art.

One of the things I liked a lot was a performance by the Ukrainian artist Volodymyr Fillipov at the opening of Art of Expression. He gave everyone in the room ice to have in their hand and talked about the time passing as a metaphor for the war dissolving from the media narratives.

The curators of Art4Ukraine also pointed out a work by a Ukrainian artist Oleksandra Verkhovska called “The Price of Freedom”. It's a photo of the artist wearing a dress made from pillowcases and sheets, which she sew directly on herself and then burned, tore and dyed the pieces of fabric to show the pain that you feel during the war and occupation. She called it “bodily psychological work”.

Anastina: There is something about being in a restricted situation and the creativity that comes about with your limited resources. To create limitations is a methodology often used in art studies in order to broaden perspectives and increase creativity. Nevertheless, it was devastating to see artists involuntarily in restricted situations. When I saw Oleksandras work for the first time and read her story of living under bombings in Kyiv, I was very moved, it was very powerful.

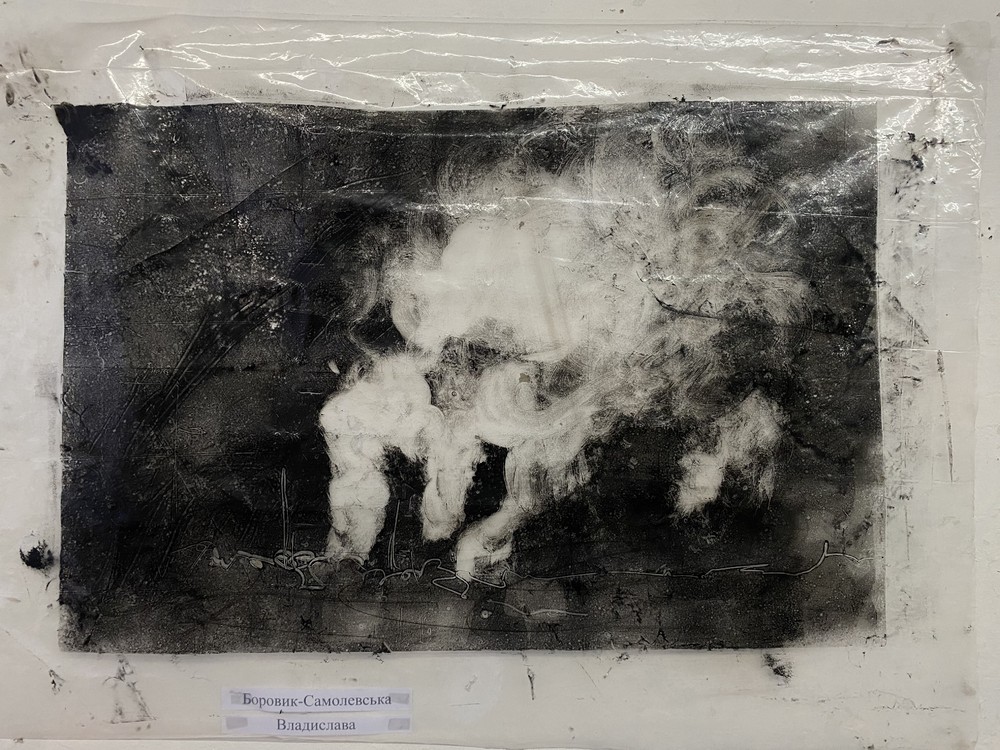

INSERT WORKS OF VLADYSLAV RIABOSHTAN

During the second auction Art4Ukraine raised 68885,74 NOK. As for now, the organizers are taking a break before planning for next year.

Lea: This initiative made us focus on more solidarity in general. After Covid broke out, we became even more individualistic, vulnerable and alienated than before here in Norway. This process of working together to help other artists in Ukraine made us open up a completely different perspective of the artwork and art community in general. And we decided to keep it going in this project.

CREDIT

1. KUNSTPLASS

Anastina Eyjolfsdottir, Anna Sofie Mathiasen, Betina Torbjørnsen, Bill Billekvist, Cecilia Riis Kjeldsen,Christian Messel, Emil Kjærneli, Geir Moseid, Geir Yttervik, Gonçalo Carvalho, Hedda Grevle, Ida Ekblad, Ingeborg J. Tysse, Ingeborg Skåland Eriksen, Io Sivertsen, Jan-Eric Wold Skevik, Jara Marken, Jo Mikkel Sjaastad Huse, Jon Benjamin Tallerås, Julia Boracco, Julia K. Persson, Julie Hrnčířová, Ilija Wyller, Kasparas Brazovskis, Katarina Skjønsberg, Lea Ye Gyoung, Madelen Isa Lindgren, Maria Bårdsdatter Foslie, Marianne Toppe, Marthe Kampen, Michael Laundry, Mingxuan Tan, Nanna Amstrup, Natasha Tzeliuba, Nikola Lieblein Røsæg, Nikolai Kaasa, Oksana Kazmina, Oksana Kazmina, Pearla Pigao, Per Ellef, Ragnhild Nes, Sashko Protyah, Stan D’Haene, Suyoung Yang, Svitlava Shymko, Tarik Hvidsten Hindic, Terje Vestervik, Thomas Sæverud, Thyra Dragseth, Tim Kliukoit, Vilde Rolfsen, Ylva Greni, Maria Storm-Gran.

2. NOBEL PEACE CENTER

Adin Mušic, Alexander Chepelev, Mutafory Lili, Anastasiia Yakovenko, Ane Barstad Solvang, Charlotte Tjomsland, Emily Rubina Johnsen Sletaune, Geetanjali Prasad, Geir Moseid, Hans Petter Haraldsen, Herman Brede Enkerud, Ida Ekblad, Ilija Wyller, Jakob Kirkevaag, Jan Eric Skevik, Julia K, Persson, Julie Olsen, Karina Synytsia, Katarina Skjønsberg, Lisa Edetun, Lydia Soo Jin Park, Magdalena Kotkowska, Maria Pelkonen, Matilde Wedzicha, Md Wahiduzzaman Bhuian, Mingxuan Tan, Mitra Shamloo, Mykhailo Zubchaninov, Naeun Kang, Nanna Amstrup, Nikolai Kaasa, Oleksandra Verkhovska, Olena Slavova, Olha Lisowska, Olia Kravchyshyna, Per Ellef, Pernille Sandberg, Betina Torbjørnsen, Reza N. Roshandel, Sunniva Havstein, Vlad Nikorchuk, Vladyslav Riaboshtan, Volodymyr Filippov, Lena Heggelund, Yachmin Sofiia Oleksandrivna, Zirui Liu, Emil Ellefsen, Geir Yttervik, Maria Storm-Gran, Emil Kjærnli, Jara Marken, Christian Messel, Nikolai Liebein Røsæg, Thomas Sæverud, Jon Benjamin Tallerås, Tim Kliukoit, Michael Laundry, Ragnhild Nes, Knut Bry, Pernille Nadine, Bill Billekvist, Cecilia Riis Kjeldsen, Ylva Greni, Suyoung Yang, Rudolf Terland Bjørnerem, Hanna Asefaw, Andreas Røysum, Marina Hobbel, Julia Musakovska, Ija Kiva, Oleh Kotsarev, Jurij Zavadskyj, Benjamin Lønne Røsler, Nanna Lundevall

HELPERS

Bendik Storbekken, Herman Breda Enkerud, Klara Døving, Magnus B. B. Lysbakken, Christa Barlinn Korvald, Martin Oreste Pecori, Emily Rubina Johnsen Sletaune, Simen Formo Hay, Ylva Greni Gulbrandsen, Ylva Elise Gülpinar, Eline Mannino

SPONSORS

AHO, Artifix, Bortenfor, Frittord, J2, Kunstplass Contemporary Art [Oslo], Nobel Peace Center, Padon, Råkk and Rålls

Solidarity Screenings

In June we started Solidarity Screenings, a video program which provides an intimate portrayal of people caught amidst the war, occupation and forced migration. Made to preserve and develop the evidence, reflections and feelings, all of the video works have been created by visual artists based in Ukraine after the start of the russian invasion. The works show the ordinary life of people that changed overnight, when millions of peaceful citizens became victims, spectators and participants of the full scale warfare, humanitarian crisis, volunteer movements, migration and resistance.

The films have already been shown in Amsterdam, Prague, Riga and Malmo and are planned in other European cities.

The program is curated by Serge Klymko, founder of Emergency Support Initiative.

Museum of Strength

The exhibition "Museum of Strength" by Nikita Kadan took place in November as part of the residence Sorry No Rooms Available, hotel Intourist-Zakarpattia.

"We all perceive each other as objects. This, as I remember, is how Graham Harman put it.

The state of freedom means atomization, dispersal of our community, our collective self. The state of war consolidates this self, brings us closer to homogeneity. We are being exterminated on the basis of an attribute we share and unite around this attribute. It forms the foundation of our resistance. Opposition is rooted in a subject. It is carried out on behalf of a collective identity, someone or something chosen, agreed upon. Resistance is object-based. It’s offered by bones, trees, concrete structures, everyday habits, social relations not regulated by formal contracts, soil, air. In times of war, bodies, intonations, habits, the timbre of thinking change. Within seconds, bones and internal organs can be mixed with glass and concrete. The rapidly evolving situation presents us with ever new traps of conformist solutions. Consciousness readjusts its relation to the idea of the future. Body experiences continuous surges of adrenaline.

A room-dwelling Atlas can also have dignity: support the walls, hold up the ceiling. The state of elastic resistance may look like immovability. Crucially, though, one should not overuse the phrase “cultural front”: never forget where the real front is.

The museum is “turning war into history” in real time. The possibility of a museum that preserves peripheral narratives. Peripheral lives. At the same time, the museum is also a court of law.

I recall a German friend who phoned me in the first week after the 24th, hinted at “red lines” and said it’s better to immediately switch to guerrilla fighting rather than accept weapons from the US. He can go fuck himself, of course.

Matter thinks by producing resistance".

Nikita Kadan

Music video by Anastasiia Suprun-Zhyvodrova

In the video, you can see Oleksandr Shchetynskyi, a Ukrainian composer of contemporary classical music. He wrote the piece he performs in the video at the age of 13. Before the war, Anastasiia was preparing a series of documentaries which included an episode about Oleksandr Shchetynskyi; the footage featured in the video was shot in the autumn, but, according to Anastasiia, after February 24 it gained a new meaning.

“An empty hall, where people could sit, but only ghosts are present now; composition; tempo and rhythm — eerily, it turned out that everything fits the current context: the reality where a huge number of innocent people died. For me, this is not just statistical data from the news: many friends who remained in Kherson incurred harm, some of my classmates went missing, one acquaintance was torn to pieces by a shell. I find it difficult to wrap my head around the staggering civilian losses,” Anastasiia says. “With this video, we wanted to urge people to speak up. I have friends and relatives in Europe: Malta, Germany, the Netherlands, Lithuania, England. At first, everyone enthusiastically supported us, but later people got tired of being distressed by traumatic events, photos and videos. However, tragedies and horrors continue to happen in Ukraine; we must remember this and talk about it,” she adds.

Anastasiia comes from Kherson, and her family still lives there. Together with her husband, Anastasiia has lived in Kyiv for the last 8 years; she was there when the war started. A neighbouring house was badly damaged by the wreckage of a downed missile, and windows in her flat were blown out by the blast wave. Now Anastasiia and her husband live in Cherkasy, where she is volunteering and gradually returning to work.

“Right now, art exists in a suspended state, because we realise that our army needs to be supported first. My brother and friends are at the front now, so I understand that funding for culture and art is not a priority at the moment, but I am convinced that they constitute equally important elements of the struggle,” she says.

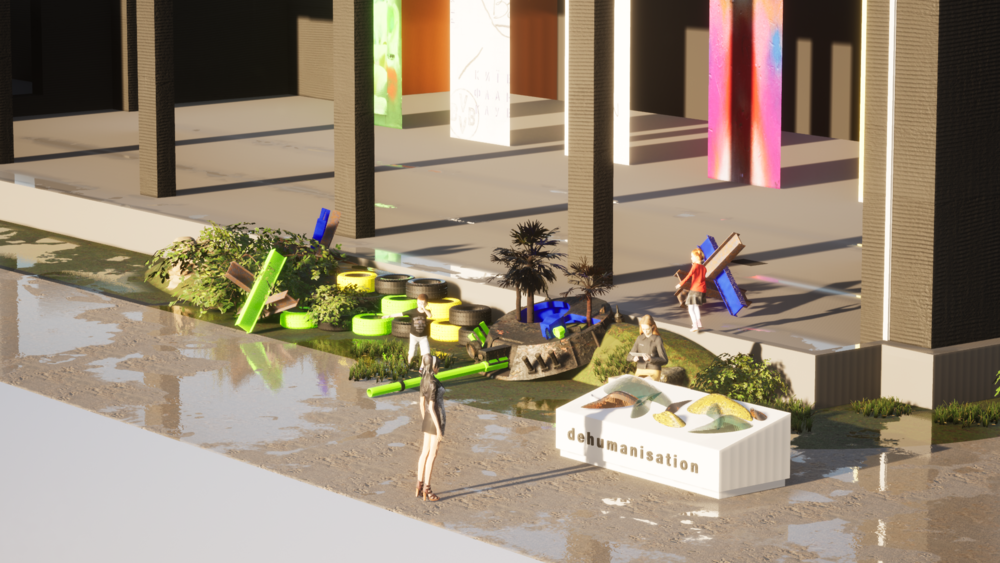

Dehumanisation

The event featured poetic “drop readings”, a spontaneous graffiti session and the exhibition of 7 artworks by Roman Mykhailov and Alisa Bondarenko, Obies, Commercial public art, Twintwin_tattoo, Onek, Alisa Shampanska, Sestry Feldman and Taia Kabaieva.